What my radical Jewish grandparents taught me about survivorhood, healing, and resistance

Learning about my Jewish grandparents' activism helped me embrace my Jewish and gender identity. It also taught me about the revolutionary nature of Jewishness itself.

I’m a mom. I happen to be trans—although I did not come to realize this until I was nearly in my fifth decade. I’m also Jewish. I've been aware of this for some time—although I did not become comfortable with it until relatively recently.

Like a lot of Jewish people, I have a complicated history with the label. For a long time, I didn’t even like the label being applied to me.

Like a lot of Jewish people, I’m not an expert on all things Jewish. I am certainly not an expert on every Jewish experience.

Like a lot of Jewish people, I know a lot about being an outsider.

Like a lot of Jewish people, I know a lot about being hated. I know we’re not alone in this. I know we all do things every day, whether we want to or not, that help perpetuate a system of hate and injustice.

I simultaneously experience several intersections of oppression and many intersections of privilege. I have light skin. In many situations, I “pass”—whatever that might mean. In other situations, I don’t. I have a college education, and thanks to debt relief and a career in nonprofits, I am no longer in hock for that education. I have had a somewhat lengthy, by contemporary definitions, career in nonprofit arts. I was born and live in the United States, speak English fluently, own a house, my children are healthy, and more days than not, I know I can put dinner on the table.

We all play a role in perpetuating oppressive systems. Through actions we take—or through actions we choose not to take. I think of this every time I get in my car and drive. I think about how, when I press the gas pedal further, I’m personally poisoning the atmosphere just a little bit more. Or with every piece of trash I throw out. Or every item I order from Amazon or some other big box store simply because that’s what I can afford.

I’ve spent hours searching for “ethical clothing” brands, more sustainable packaging, or environmentally friendly toys for my kids, only to find that, while such things are lovely, I can’t afford to shop in exclusively “ethical” and “sustainable” ways.

I suspect most people can’t. That feels like part of the trap.

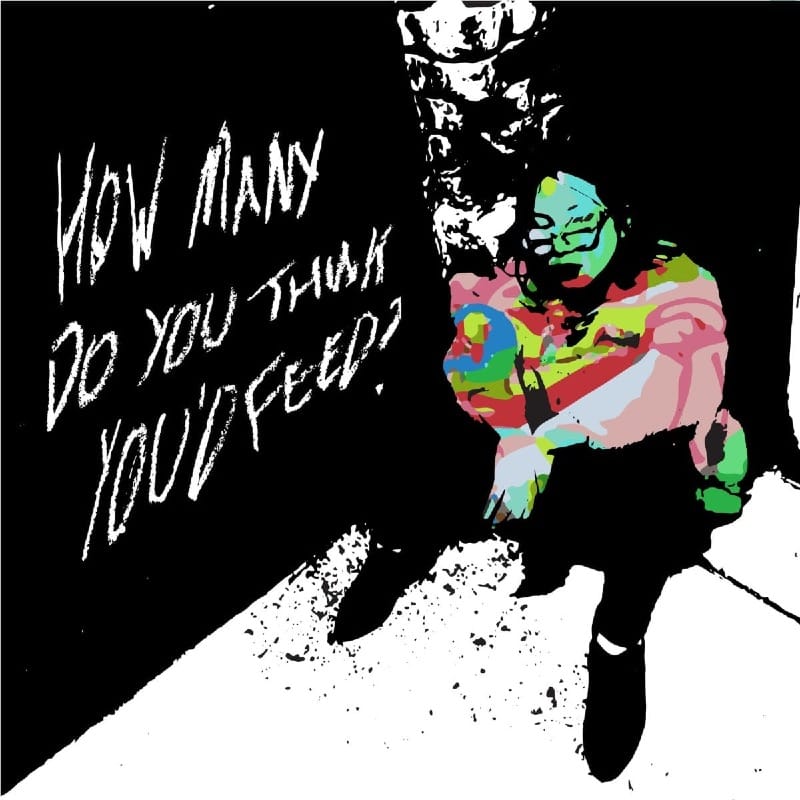

It’s overwhelming, and it can make us feel powerless. If everything we do just feeds oppression for someone, somewhere, then why bother?

Embarrassingly, I didn’t see myself as a feminist until I began my transition. On one level, I was always more than a little creeped out by cisgender men who called themselves feminists, because it struck me as ingenuine at best, or at worst, a tactic to try to get into someone’s pants. During the over two decades I was locked into a physically and psychologically abusive relationship, I was strongly discouraged from discussing anything resembling politics, and the progressive tendencies that had started developing in my adolescence were buried deeply under trauma. Another thing that got buried was my Jewishness. I had felt for years that that was one of the many reasons I was not likable or desirable as a human being.

I was told I was loud. I was annoying. I was stubborn. I was hairy. I was ugly. I had a big, red nose. I had big lips. I was too skinny. I was too flabby. I was nerdy. I was gross. I was pretentious.

I didn’t realize every single one of these things that had been levied against me was an antisemitic stereotype.

For years, I told myself that I was an atheist, not a Jew, and that the two were incompatible. After all, that was what I had been taught in my early, Orthodox-dominated education on Judaism. It didn’t even occur to me how extremely Jewish of a thing it was to try to disprove my own Jewishness using “halakha,” or Jewish law.

The year I embraced my identity as a trans woman was the same year I embraced my Jewish identity, my feminism, and my anarchism, as well as the synthesis of my skeptical atheism and spiritual faith. These things did not all happen at the same time, but they were all most certainly connected.

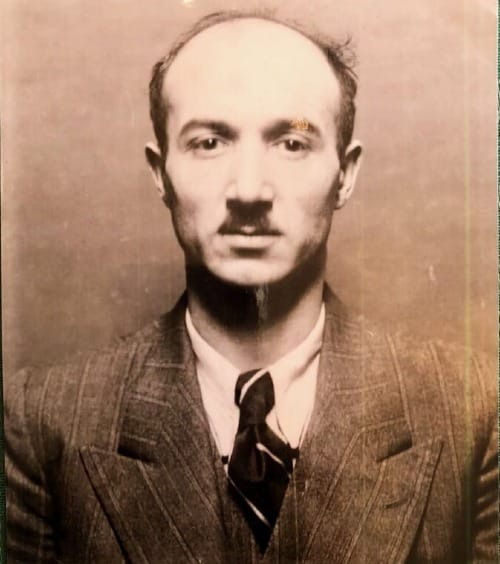

In the late fall of 2021, after I began my transition, I had an idea for a sci-fi novel—a fictionalized retelling of my grandparents’ experiences leading up to and during the Holocaust. In my childhood, I had often been told stories about my grandparents’ resistance to the Nazis, and how they had both died, fighting to the last. Now I was finally free to explore my connection to these stories as I processed my gender transition and Jewishness.

I’m sure such romanticization of their roles made it somewhat easier for my father to stomach the fact that he and his two older brothers had been left behind in the care of an eighteen-year-old gentile girl for the duration of the war.

I had wanted to write a time-travel romance in which these two revolutionaries came back to interwar Europe from some time in the future, knowing what was written for them, but with a mission to seed the future from which they came.

I figured I needed to do some research beyond the oral history I’d been given by my father, his brothers, and the few survivors among their cousins I’d had the opportunity to talk to face-to-face growing up.

Eventually, I stumbled across a video interview my eldest uncle, who is seven years older than my father, had given to the Yad Vashem Museum in Jerusalem back in 1966. As I was working my way through the interview transcript, some things I had known but hadn’t fully absorbed became a bit more real for me.

Among them was my grandfather’s involvement in the Spanish Civil War. I found myself asking, “Why would someone with two young children volunteer to go fight in a war in a foreign country?”

I had always been told as a child that my grandparents were identified variously as communists or anarchists, but this was always said dismissively because “to fight Nazis back then, that’s what you were.” As if to say, “they didn’t really believe in either anarchism or communism; that’s just what was in fashion for a young, 1930s anti-fascist.”

It seemed to me that to go fight in Spain in the 1930s, you either had to really love fighting, or really believe in your cause, or both. Fashion kills, but usually not like that.

But what I discovered changed my understanding of my grandparents—and myself—completely.

In the period during and just after the Spanish Civil War, my grandfather was a seemingly transient figure in my uncles’ and later my father’s lives. He went off to war. Came back home. Got arrested. Escaped. Worked and met with community organizers. Got arrested. Escaped. I don’t exactly know what he did during the periods he disappeared, as the narrative I received was perceived through a child’s eyes.

They eventually fled from Berlin (where my grandparents had met—my grandmother was originally from Łodz, my grandfather from Köln) to Belgium, where my father was born. While there, my grandfather and grandmother were involved in mutual aid in their community and in helping get other refugees out of Germany. In Belgium, a work permit was required to earn a living, and obtaining one was exceedingly difficult, leaving communities of refugees to rely on mutual aid. The community organized an ad hoc Hebrew school for the kids, taught out of another refugee’s apartment. My grandparents distributed forged food stamps out of their flat, and my grandmother fed groups of people as though it were a restaurant.

I grew more curious, through my grandfather’s connection to it, about the Spanish Civil War and about the International Brigades—the communists and anarchists who flocked from around the globe—who lent themselves to the cause. I learned about the flocks of passionate, dedicated anarchists, communists, and other revolutionaries who traveled from Germany, from America, from colonies across the globe, to join in the battle for liberation—not for Spain, but for global liberation. I grew more curious about the principles of mutual aid, anarchism, and liberatory theory, old and new.

It was overwhelming. There was just so much of it. I didn’t agree with all of it, but I found a lot of it felt familiar. It felt old. It felt like ancient knowledge.

A lot of it felt very Jewish.

What is a Jew? It is a hard question to answer. Some restrict its definition to a religion; others say it is an ethno-religion. These are both incomplete answers.

But I can list two things that are characteristics, unique or not, of what might variously be called either Judaism or Jewishness, characteristics that are directly responsible for the survival of Judaism against all the odds and which paved the way for revolutionary Jews like myself and my grandparents.

The first touches on this very argument: the resistance of Judaism to definition. Millions of people around the world call themselves Jews and yet have very different ideas about what a Jew is, and what our faith, our practice, our culture all look like.

The Judaism that lives and breathes in the world now, in whatever form, would be unrecognizable to a Temple Jew of two millennia ago. But the fact that all of these different practices have existed under the umbrella of Jewishness shows the resilience and strength of being able to thrive through change.

Judaism does not allow for proselytization. We should be welcoming to those who choose it, but never try to make anyone else Jewish who does not wish it. This may be seen as a weakness, particularly when contrasted with the great proliferation of Christianity over these same last two thousand years. By contrast, the world population of Jewish people has remained vanishingly small.

This is also one of the most subtle and insidious ways I observe dominant Christian hegemony seeping its way into social movements. There is this desire for greater mass, more voices, more consensus. There is a pervasive majoritarian thinking that edges a bit too close to “might makes right” for comfort. Just because a majority agrees on something, that does not give the majority moral authority. As a persistent minority, Jews know this viscerally.

Whether the desire for homogeneity among these movements is real or not, there is a very real perception that thoughts outside of accepted dogma are to be shunned. I come back to Jewish tradition, where even in the Talmud, ancient Jewish sages debated the meaning of this or that bit of Torah; differing and contradictory perspectives are recorded, regardless of whether they won their way into majority acceptance and practice. The holding of multiple conflicting, even minority, points of view is central to Jewish culture. That is the strength of the diaspora.

The second unique characteristic I’d like to touch on is the practice of “ḥevruta,” a form of communal study. These are groups of no more than five people. The word comes from the same root word as friend (“ḥaver”) in Hebrew.

For most of my time in elementary school, I constantly felt othered in one way or another. Because my parents were immigrants. Because my mother was a convert. Because I was a “smart kid” and a nerd. Because I was bad at sports. But in sixth grade, my class dwindled down to just five kids, and suddenly there were no in-groups and out-groups—we were one group.

What an ingenious way to perpetuate a culture that had lost its center of gravity. When the second temple was destroyed all those years ago, surely Jews feared that this was the end. The end of their people, the end of their faith, the end of the power of their divinity.

And yet it survived. When we lost the temple, we lost the remnants of hierarchy. Judaism was slowly transformed from temple Judaism to Rabbinical Judaism, and instead of having priests who played intermediary with God, we had rabbis who were teachers, keepers, and purveyors of ancient knowledge.

We learned how to build and maintain communities in the face of not only oppression but also the risk of complete annihilation. Societies of mutual aid rose up—communities centered around learning and shared culture. When the dominant culture around us denied the legitimacy of our livelihoods, our stories, we made our own and reveled in them together.

It is these unique factors that make Judaism akin to a resistance movement that has survived for millennia and, thus, has many lessons to teach us all on resilience and persistence in the face of assimilation and hegemony.

I think that is at the core of why, so often, we see Jewish people disproportionately represented amongst the ranks of those fighting for social justice, fighting for the rights of the outsider, and the oppressed. My grandparents must have felt this pull, this drive, to fight alongside people they saw as comrades among the ranks of the oppressed, fighting against the faceless machine of fascism that threatened to march over—notably in Spain, Italy, and Germany—but also across the entire globe. They understood that our liberation is bound up with yours, and whether or not you will stand with us, we will stand with you—not for the sake of our liberation, but because it is the only thing we know how to do.

At this point in my exploration, I felt the burning drive to do…something. My grandparents had lived through an astoundingly trying time, and in that bleak landscape, they found and created joy in community. With my newfound freedom and liberty, I was compelled to help spread that sense of healing. In a world of trauma and injustice, I wanted to do whatever was within my power to begin to grow that healing.

I sought an alternative to what we’ve been conditioned to think of as “justice” for survivors. I did not wish punishment for my abuser, as I believe that punishment only sustains cycles of violence. Violence breeds violence. Oppression breeds oppression. I wanted to see healing—as the smallest step towards healing the world—towards “tikkun olam.”

I wanted, for a time, to see my abuser heal. That came out of my experience with the so-called justice system in the United States. When I was asked to confront what my idea of justice would be for the person who abused me for over two decades, I didn’t really want to see them punished—I didn’t see how that would make anything better. I didn’t think they would be able to ever repay me for what they’d taken from me.

I saw through the work of Jewish radicals like my grandparents that healing was possible. Seeing that my own family had participated in the kind of revolutionary community building I wanted to be a part of—a solution that healed wounds rather than seeking vengeance for them, that answered with love and aid and care rather than using community resources to inflict punishment—led me to start engaging in mutual aid work. I would spend hours, days raising grocery money, or rent money, or utility money for people in need.

I tried to create something new. Or at least something I hadn’t seen before—yet something those who came before me were striving for. That they died for.

I wanted to create the work/play-place that I would want to inhabit in a liberated world, and I devoted large chunks of my time over six months to this effort. Setting up the expectation that I was willing and able to let this take over more and more of my time led to a toxic loop and eventual burnout. The realities of life under capitalism kicked in again, and eventually the effort collapsed under that weight. But I learned a lot of lessons from it, and one of those was about the Jewishness of what I—and my ancestors before me—were striving for.

The thing we sometimes fail at most is calling out antisemitism in all the numerous places it rears its head, just as racism and white supremacy dominate the landscape. It can seem like one or the other thing is the “more severe” problem, but the truth is that all bigotry is interrelated, and we cannot set one aside to address another. Time and again, we see how antisemitism feeds white supremacy, and how white supremacy feeds antisemitism. These battles cannot be separated from each other, and no part can be minimized. All bigotry must be uprooted and examined, inside us and out. We must closely examine our biases and prejudices until we are no longer looking away, diminishing, and saying, “It’s not a big deal.” It’s hard to accept, but until we do, we cannot dismantle systems and adjust our relationships to each other, to our communities, to our world.

Today, when so many of us, Jewish or not, cry out to have a voice, when so many of us feel that voice stifled, when dominant culture tells us our art is not legitimate, or credible, or credentialed by the proper authorities—in resistance, we create.

I’ve been told so many times over my life that I need to “pay my dues” in order to be accepted in this, that, or the other thing I’m doing, whether it’s music, art, writing, my so-called career, but I’m done listening to that voice.

We can just do, and in doing, thrive. Resist by thriving, especially when it seems impossible.