The Jews and the Left in America: Reprint from Jewish Socialist Critique, 1979

The issues faced by Jewish Americans in the late ‘70s and early ‘80s, and their assessment of the New Left, are no less crucial to us now in 2025, having witnessed the failure of neoliberalism and the rise of right-wing populism.

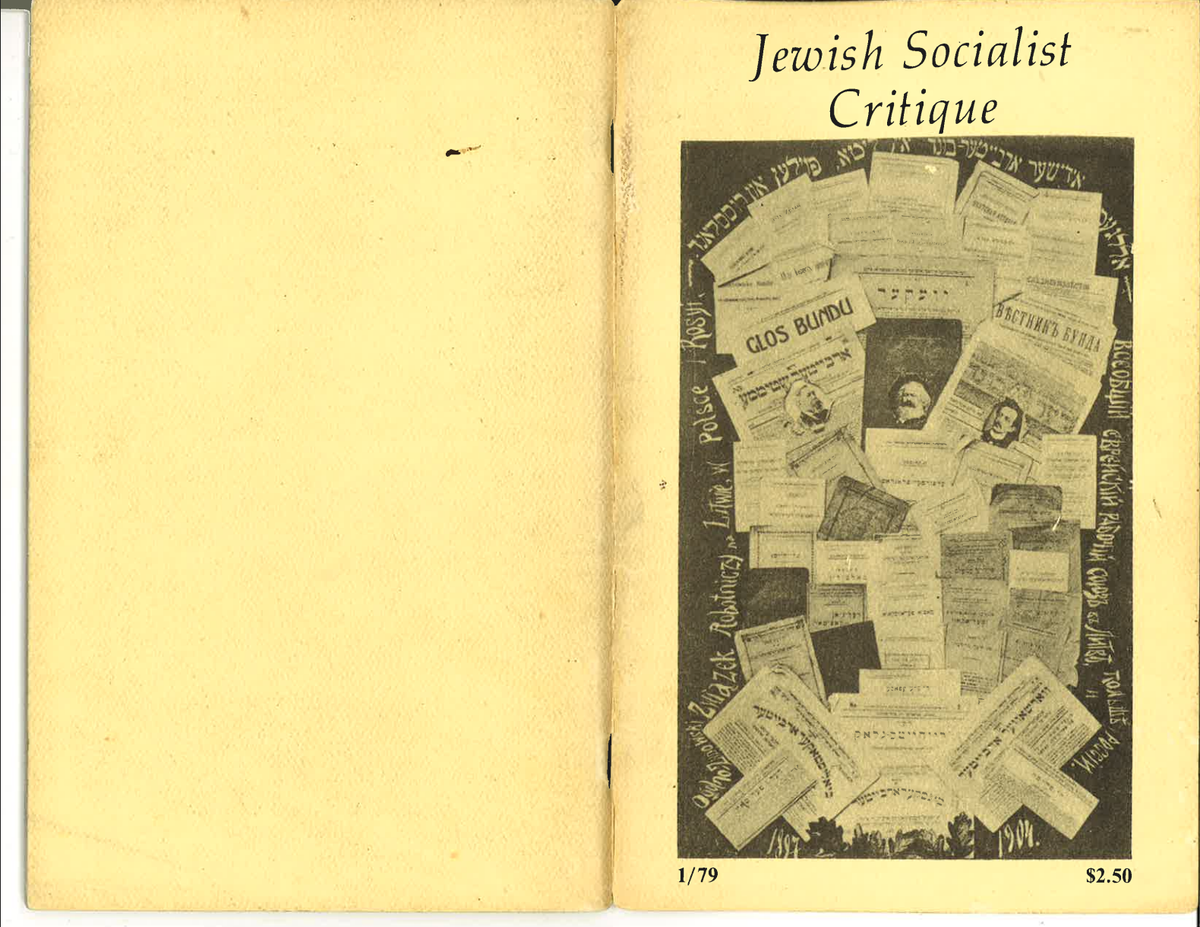

Jewish Socialist Critique was a quarterly publication, first released in the Fall of 1979, which presented “a non-sectarian but rigorous socialist perspective on Jewish affairs.” Issues focused on “political, social and economic analyses of the American Jewish community, Israel, and other Jewish communities abroad.” The magazine was printed out of Berkeley, and poetry submissions were sent to an editor in New York. From what I can find, JSC had only three runs: the aforementioned Fall, 1979 release, Winter 1980 and Spring 1980; as well as a pamphlet from 1983. (Those links all redirect to pdf files.)

The overarching theme of Jewish left-wing political history presented here is not that Jews were attracted to these positions because of religious or ethical teachings, although those certainly can support left wing politics; but because of the historic convergence of Jewish oppression by both class and ethnicity, and finding in left wing politics the tools to individual and collective liberation. Young Jews’ participation in the New Left was not necessarily due to what they learned in Sunday School, but was passed on to them red-diaper style by their socialist parents; or it was gleaned from Marxist texts they read in the radical ‘60s; or class analysis was discovered the old fashioned way: face to face with the brutalities of capitalist exploitation.

It is also worth noting another form of Jewish politics that grew in that radical era: Zionism. Israel’s victory in the Six Day War in 1967 led to a resurgence in explicitly Jewish politics, and young Jews attempted to merge it with the identity politics of the time, a la Black liberation, for example. There were small groups formed such as the “radical Zionists” who were left wing Zionists and couched their politics in terms of national liberation. This supposed link between liberal/left politics and ethno-nationalism continues its tenuous grasp over many Jews today. It wasn’t until 2019, over 20 years after it was founded, that Jewish Voice for Peace became explicitly anti-Zionist.

I have wanted to transcribe these issues of Jewish Socialist Critique since I discovered them on marxists.org nearly a decade ago; they were an inspiration to me when some friends and I started the short-lived Jewish Solidarity Caucus, which was vaguely DSA-related, back in 2017. I remember fondly inviting one of the editors, who lives in New York, to one of our meetings. Discovering these writings was almost a spiritual experience for me, which is very rare for an atheist; the dialectical and materialist approach seemed fresh in comparison to the mostly liberal/ethical critiques that many Jewish activists still espoused. I obviously find the Bund inspiring – Vladimir Medem wasn’t coming to any of our organizing meetings, however. Jewish Socialist Critique was nostalgic, but not overly so.

The issues faced by Jewish Americans in the late ‘70s and early ‘80s, and their assessment of the New Left, are no less crucial to us now in 2025, having witnessed the failure of neoliberalism and the rise of right-wing populism in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis and two elections of Donald Trump. The editorial board of Critique asks, “what does it mean to affirm ourselves as Jews and socialists?” Indeed, the lack of a fulfilling political life as espoused by both the U.S. Jewish community and mainstream Democrat politicians leads us to a similar critique, generation after generation.

-- Lane Silberstein

New York, NY, 2025

Statement of the Editorial Collective - Fall, 1979

During the last three decades the world has seen the rise of numerous national liberation movements against colonialism and imperialism. And in recent years the corporate bourgeoisie in the United States has witnessed serious challenges to its prevailing system of racism and cultural oppression at home. Blacks, Hispanics, Asians and Native Americans have engaged in organized struggles to resist the material exploitation they experience. In this process they have adopted their own ideological and organizational forms in order to affirm their identities and preserve their cultural traditions.

The relationship between Jews and socialism is rooted in the ways in which Jews in czarist Russia and the United States confronted capitalism during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

The advanced capitalist world has also been confronted by the movement for the liberation of women. This movement has built itself into a political force against male supremacy – a linchpin of capitalist oppression. Socialist-feminism has made important contributions to understanding the system of power which stems from both the class relations of production and the sexual hierarchical relations of society.

The experiences of ethno-national groups and women demonstrate that oppression involves more than economic exploitation. The left thus confronts an urgent political task: to develop socialist theory that encompasses the realities of women’s lives and the lives of racial and ethnic minorities. Just as the struggles against women’s oppression and racial/ethnic oppression cannot realize their full potential without a strong socialist movement in America, so the left cannot grow without a theory that comprehends and incorporates these forms of oppression.

The development of such a theory will not be easy. Indeed, the problem of how a revolutionary theory can emerge from the day-to-day practice defined by the existence of capitalism has long bedevilled socialists. In the United States, as elsewhere, the specific dilemma of integrating questions of class with those of culture has remained unresolved. Jews, in particular, have been directly concerned with this dilemma. The failure of the left to develop a sophisticated and coherent theory of ethnic consciousness has contributed to the tumultuous relationship between American Jews and the left; Jewish involvement in leftist activity has fluctuated partly because of the inconsistency and misunderstanding characteristic of the left’s treatment of Jews and Jewish issues.

As the Jewish community grew wealthier, and diversified its class positions, it tended to dwell more on issues of Jewish awareness and less on the problems of social transformation. Gradually, socialist ideology was overshadowed by the outlook of the Jewish bourgeoisie.

To be sure, the degree of commitment to socialism among Jews is not merely a function of the left’s attitude toward “Jewish” concerns; the class position and interests of Jews is no less relevant in determining their political stance. But the actions and policies adopted by socialist parties and movements in the United States clearly affected the measure and support that they received from Jews.

Today, as well, many Jewish socialists, like socialists of other groups, take into account the left’s position on ethnic consciousness in their own political action. The experience of many Jews in the new left in particular has made them wary of socialist organizations and movements that champion self-determination for national minorities yet ignore the desire for cultural autonomy among ethnic groups or that fight racism yet overlook the existence of antisemitism. In order to gain a better understanding current among Jewish socialists it is necessary to consider the past relationship between Jews and the left in the United States.

Jews and the Left in the United States

It is well known that Jews have participated heavily in socialist organizations and movements in the United States. This participation has often been erroneously attributed to the Jewish religious and ethical tradition. In fact, however, the relationship between Jews and socialism is rooted in the ways in which Jews in czarist Russia and the United States confronted capitalism during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. In Russia, by the turn of the century, Jews were for the most part an exploited proletariat as well as an oppressed people. The roles of the czarist government in the economic and ethnic oppression of Jews made it easy for Jews to concentrate their antagonism on the state -- the ultimate cause of their plight. As a result, significant numbers of Jewish immigrant workers who streamed into the United States before the First World War carried with them a strong identification with the economic and political ideas of socialism.

This identification was strengthened in the United States where the Jewish proletariat, like other segments of the working class, were ghettoized in similar occupations and geographic areas, and faced exploitation as a class and oppression as an ethnic group.

At the same time, however, this particular working class possessed a specifically Jewish identity. For the masses of Eastern European Jews developed a rich popular culture based on Yiddish supported by literature, the press, music and the theater. Largely a working class culture, Yiddishkeit embraced intellectuals and literary people as well as the Yiddish-speaking masses. These workers and intellectuals -- a considerable number of immigrant Jews were both at once -- were linked by reading groups, classes, choruses and drama troupes in which radicals and socialists prominently figured.

The Jewish working class was marked by a tremendous capacity for sacrifice, intense feelings of solidarity, and a considerable faculty for organization. The strength and militancy of these Jews may be measured by reading accounts of of the 1909 shirtwaist makers’ strike, the 1910 cloakmakers’ strike, the 1912 furriers’ struggle, and the 1912-193 strike of 100,000 men’s garment workers that led to the founding of the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America. Moreover, the Jewish workers provided a key source of support for the Socialist Party in the years prior to 1920.

In 1953 the Anti Defamation League of B'nai Brith, the American Jewish Committee and the Jewish War Veterans offered their cooperation and files to the House Committee on UnAmerican Activities (HUAC).

After World War I, a number of factors began to work against the links between the Jewish community and the left. (Of course, the popular movement for socialism as a whole was weakened after the war due to government repression and reforms, as well as the failure of trade unions to pursue a class-conscious perspective). The rapid decline in immigration of working class Jews (as a result of the immigration laws of 1921 and 1924) and the dramatic socioeconomic changes due to occupational and educational mobility began to dilute the strength of a working class movement among Jews in the US. As the Jewish community grew wealthier, and diversified its class positions, it tended to dwell more on issues of Jewish awareness and less on the problems of social transformation. Moreover, the consolidation of Jewish communal and philanthropic organizations -- especially the federations -- marked the increasing unification of the American Jewish community under the leadership of a small number of prominent Jewish families and individuals. Gradually, socialist ideology was overshadowed by the outlook of the Jewish bourgeoisie. Meanwhile, the greatest political change to the stance of the Jewish left from within the American Jewish community came from the Zionists; the development and importance of Zionist organizations and the weight of Zionist sentiment within American Jewry were key forces in removing the left from centerstage on the American Jewish scene.

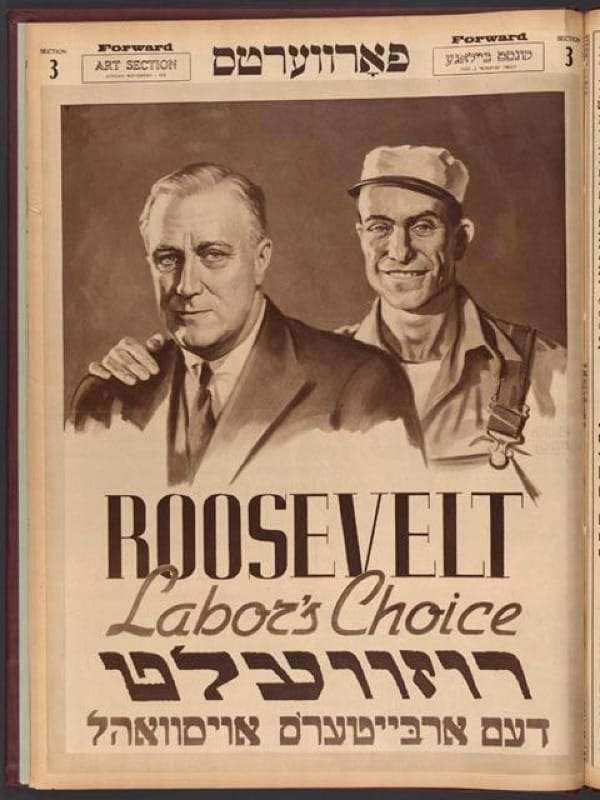

Yet the Jewish labor movement and left subculture continued to exist during the interwar years. The primary institutions of the Jewish left were the labor fraternal orders (such as the Workmen’s Circle and the International Workers Order), and the left Yiddish-language press (such as the Jewish Daily Forward and the Freiheit). Jews comprised a relatively large proportion of both the Communist and Socialist Parties throughout the 1920s and 30s. Indeed, numerous Jewish workers and professionals served as leaders and activists in socialist organizations and parties before the Second World War. During the Depression, Jewish students in particular developed an ideology and political commitment that reflected their proletarian status.

The terrible trauma caused by the genocide committed by the Nazis against European Jewry in WWII, and the founding of Israel shortly thereafter, consolidated the emphasis on Jewish spirit among American Jews. Indeed, the extent to which Israel heightened Jewish consciousness can be measured by the fact that Communist Jews developed strong feelings of attachment to the Jewish people and Jewish culture during the war years and up to 1949. The Soviet Union’s early support for the creation of Israel in the United Nations and its aid to Jewish forces in the 1948 war also served to bring Communist Jews closer to the American Jewish community.

With the advent of the cold war, however, the temporary detente between Jewish Communists and the Jewish community came to an abrupt end. Organized American Jewry, along with other sectors of American society, was plunged into the hysteria of McCarthyism. American Jewish organizations rushed to identify and remove actual and suspected Communist individuals and groups from the Jewish community. The arrest and trial of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg in the early 1950s was particularly frightening to Jewish establishment leaders as the campaign of their supporters emphasized their Jewish background. Thus, for example, in 1953 the Anti Defamation League of B'nai Brith, the American Jewish Committee and the Jewish War Veterans offered their cooperation and files to the House Committee on UnAmerican Activities (HUAC). At the same time, however, there were many courageous Jews who refused to participate in this witch hunt and thereby risked their own positions in the Jewish community.

Meanwhile, during the post-war economic boom, more and more Jews were being recruited into higher status jobs. In addition to their increasing membership in the professions and petty bourgeoisie, many Jews gained managerial and administrative positions in business and public service. Yet Jews in considerable numbers continued to participate in progressive movements and organizations which sought aims not directly compatible with their economic interests. The most dramatic example of such involvement was the role of Jews in the New Left.

Born amid the desegregation struggles in the South and among new militant groups on campuses, the New Left was a decentralized movement that practiced, at least in its early years, participatory democracy. It was a movement with many Jewish leaders and a significant Jewish presence. Indeed, studies indicate that approximately one-third to one-half of those involved in the New Left were Jewish. Significantly, the majority of those Jews active in the early years of this movement – from the late 1950s through the mid-1960s – had old left backgrounds.

Young Jews in particular, both democratic socialists and social-democrats, were attracted to the humanistic and civil libertarian positions of the New Left. Yet many of them felt a continual tension between being a part of the Jewish community (whose major organizations were shifting to the right), and being active in the left. A mass-based movement, the New Left was marked by many political conflicts and splits. As certain groups embraced doctrinaire party positions and attacks on Israel became commonplace, some Jews withdrew from the movement. Many others, however, continued their radical involvement: moving to feminist struggles, community organizing, and union activity.

The issue of race relations was crucial to the Jews’ involvement in the New Left. Jews played a key role in the early civil rights movement, both as activists and leaders. Jews – like other whites – left the civil rights movement as blacks sought control of their own organizations. Moreover, as the struggle of blacks moved attention from civil rights in the South to economic conditions in the cities of the North, class conflict divided major sectors of the black and Jewish communities.

The bitter polarization of these two communities – especially in New York where charges and countercharges of racism and antisemitism abound – resulted in strong reactions on the part of Jewish leftists. These reactions depended on the nature of their involvement in the new left. Many of those on the forefront consciously rejected their identification as Jews and condemned the Jewish community as reactionary; others – primarily left-liberal sympathizers – were repelled by the positions on both sides in the conflict and reduced their political activity while retaining their political ideals; and some became so paralyzed by the confrontation that they abandoned the political arena altogether.

For example, by 1968, leading Jewish organizations had begun to oppose black demands for community control which many Jews regarded as a challenge to their own socioeconomic security. These demands were also regarded as affronts to the civil libertarian and liberal positions which many Jews held. Thus, these Jews defended the organized conservative response to the Ocean-Hill-Brownsville controversy in 1968 in the name of liberalism and traditional Jewish support for trade unions.

Unfortunately, few Jews or Blacks have been able to perceive the extent to which their conflicts stem from a social system that fails to meet human needs – educational or otherwise. The furor over community control of schools was a classic case of the way in which Blacks and Jews are pitted against one another in this system.

A more recent example is the Andrew Young controversy in which an almost hysterical division has been encouraged between these two communities. Many Blacks were outraged by the pressure exerted by what some term the “Jewish lobby.” It must be recognized, however, that the major Jewish organizations – the so-called Jewish lobby – do not speak for all Jews; many Jews not only favor talks with the PLO but support a two-state solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. It is precisely on such issues that the Black and Jewish radicals must unite. We cannot allow the conservative elements in our community to speak for us.

It has become evident during the last decade that the shift in the class composition of the American Jewish community that occurred during earlier decades has engendered a conservative ideology and political practice within leading Jewish organizations and among many individual Jews. A number of Jewish intellectuals and public figures have symbolized and legitimized the rightward trend in the Jewish community. Figures such as Henry Kissinger, Arthur Burns, and Milton Friedman, have been the most notable of the influential conservative Jews. Moreover, a number of Jewish intellectuals who once involved themselves in liberal and leftist activities are now grouped around conservative journals such as Commentary, and insist that the interests of the Jews lie in supporting right-wing Democratic senators. Others, like Irving Kristol, have associated themselves with reactionary think tanks such as the American Enterprise Institute.

We believe our socialism is unavoidably linked to our immediate backgrounds, which includes our Jewishness. We identify particularly with those Jews who in recent times – the eras through which our parents and grandparents lived – resisted the havoc of capitalism and fascism.

The rightward movement of American Jews must be placed in its historical context. Although Jews have become more conservative in the last decade, so have many other groups in American society – if not more so. In comparison to most other ethnic groups, a majority of Jews in these years continued to hold progressive stands on most political and social issues – from Vietnam to social spending.

The American Jewish community is not monolithic; it is a diverse and stratified community. There remain significant numbers of Jews as well as various Jewish groups with strong ties to radical and socialist movements and organizations. And just as it was a distinctive feature of Jewish workers in the early 1900s to cross ethnic barriers to develop bonds of solidarity with other immigrant workers, so Jewish leftists today strive to reach beyond ethnic and cultural boundaries that divide and oppress people.

Jewish Socialists and the American Jewish Community

The position of Jewish socialists is problematic today because of the relatively prosperous situation of American Jews. In the urban areas of the United States, the various minority groups are divided into a few higher status groups, most of whose members gain middle or upper strata jobs, and more numerous lower status groups whose members largely enter the working class or proletariat. The ethno-national consciousness of the higher status minority groups tends to be defensive in nature. It arises in part from the desire to overcome the remaining obstacles to their advancement, but more so to ward off threatening demands for equal privileges by lower status groups. Thus, within the American Jewish community, defense organizations engage in efforts to resist the economic and social claims of lower status minority groups. It is no accident that leading Jewish organizations submitted supporting briefs in both the Bakke and Weber cases.

The conservatism of dominant sections of the American Jewish community has prompted many Jewish socialists in recent years to renounce completely their Jewish affiliations in favor of a complete immersion in the left. To a large extent, we share this estrangement from the Jewish community. Yet we believe our socialism is unavoidably linked to our immediate backgrounds, which includes our Jewishness.

As a consequence of the general resurgence of ethnic consciousness and the specific reaffirmations of Jewish identity in the late 1960s, two new types of Jewish leftists emerged. What may be called “Jewish new left” developed in the wake of the 1967 Israeli-Arab War and the consequent tensions that arose between many Jews and the New Left. This movement was formed largely by Jews with backgrounds in American labor Zionist movements. Their politics were primarily of a defensive nature; they devoted themselves to responding to New Left anti-Zionist attacks and to ferreting out antisemitism in the society as a whole. The more they concentrated on “Jewish” issues, the more diluted became their leftist ideology and politics.

Many other Jewish leftists, who acknowledged their Jewish identity but refused to assert it in a defensive manner, began to feel the need for an organized expression of their stance. The development of this position occurred at the same time as the demise of the New Left groups and the awakening of the left to the significance of ethno-national consciousness. These Jews have been joined by others -- who had previously separated their Jewish identities from their political lives, but who now confronted the question of combining their ethnic consciousness with their politics. We are a part of this movement and aspire to further its development.

Of course, the difficulties of being at once a socialist and a Jew have a long history in the socialist movement itself. The fact that many individuals in the past have attempted to reconcile this tension and that we ourselves are grappling with it today, demonstrates the importance of this dilemma. At the same time, we do not subscribe to the “Judaic theory of socialism” that attempts to identify areas in which Judaism overlaps socialism. Rather, we wish to enlarge the perspectives of both socialism and Judaism. Ours is an attempt to foster Jewish solidarity with other social groups struggling for human freedom, and simultaneously alert socialists to the importance of addressing questions of culture and ethno-nationalism.

The Jewish consciousness of upper strata Jews often intensifies when they feel threatened with a loss of socioeconomic privilege. The Jewish consciousness of Jews who are socialist, however, is stimulated by a sense of affinity with generations of Jews who waged world-historical struggles against against various forms of oppression. We identify particularly with those Jews who in recent times – the eras through which our parents and grandparents lived – resisted the havoc of capitalism and fascism. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, working class Jews in Russia and the United States waged battles against class exploitation. And during the 1940s, Jewish leftists militantly resisted the Nazis – in the underground organizations of western Europe, in the ghettos and death camps, and in the ranks of Eastern European partisan forces.

We also feel the tragedy of our people’s persecution and extermination brought about by the specific form of oppression known as antisemitism. To many, the history of antisemitism is all too familiar. What is not so well known, however, is the way that antisemitism operates in the United States today. The general population, as well as many leftists, have not understood the necessity of separating Jews’ actions as Jews from their actions as representatives of class interests. Jews in the petty bourgeoisie, for example, are seen, critiqued, and attacked as Jews rather than as members of a certain class stratum. In this journal we will discuss other ways in which antisemitism operates in the United States.

As Jewish socialists we welcome the current attempts on the left to develop a socialism with a broader perspective. Until recently, socialists generally restricted themselves to class issues; cultural, sexual, and ethno-national questions were often seen as secondary to the central task of economic transformation. In the past decade, however, the left has gained a heightened appreciation of these questions, and is now dealing with concerns which were previously excluded from traditional socialist theory and practice. For generations there have been Jews committed to socialism. But socialist movements and organizations have not always been committed to accepting them as Jews as well as socialists. In earlier periods Jews were regarded as a national minority and organized parallel socialist parties. In the New Left, on the other hand, Jews participated at the heart of the movement but were scarcely acknowledged as such publicly. Now we are prepared to pursue our involvement in the socialist movement, defining and asserting ourselves as Jews.

We have no desire to limit ourselves to narrowly defined “Jewish” concerns. We recognize that the dominant forces in the United States seek to encourage ethno-nationalism as a base for political action in order to inhibit the development of class consciousness across ethnic lines. If socialists are to thwart this strategy, all forms of ethnic chauvinism must be fought. Most importantly, we must support those forms of ethno-national consciousness that foster class consciousness in so far as oppressed groups oppose the institutional racism of the ruling class. Third World struggles against Bakke and Weber are outstanding examples of actions that stimulate class consciousness. Furthermore, in the course of these struggles, we learn both how much divisiveness remains among the working class and the extent of solidarity we have reached so far.

In sum, our position as secular Jewish socialists affirms the possibility of a broad-based socialist movement which can transcend the limitations of ethno-nationalist interests while at the same time acknowledging the significance of ethno-national consciousness in itself and for the movement. Such as task will be difficult; but an effective socialist presence in the United States depends upon its completion.

American Jews, Israel, and Zionism

During the Second Temple period, the Jewish people became scattered throughout the ancient world. Aside from the Jewish centers of Palestine and Babylon, there were numerous Jewish communities throughout the Roman Empire. By the end of this period, the Jews that lived under the rule of Rome actually held a more important place in Jewish life than the previously dominant Babylonian Jews. While these Jews were organized as separate communities they sustained contact with, and maintained spiritual attachment to, the Jews of Palestine and Babylon. Indeed, all of these communities served as mutual guarantors.

The relationship between Jewish communities in more recent times, however, has been markedly different. Many Zionists have called into question the intrinsic worth of the “diaspora”: they view Jewish communities throughout the world as mere appendages of Israel rather than as actual participants in the life of their own countries. They contend that the cultural life of “diaspora” Jews is marginal and on the way to extinction.

The fact that the Jewish community has taken its place within the center of American bourgeois culture and values is precisely why a socialist critique, not a Zionist ideology, is the demand of the current historical moment.

The assertion that the Jewish “diaspora” is unnatural and worthless can only alienate those Jews who are interested in a specifically Jewish cultural revival in their own homelands. Most Jews reject the very notion that lives are being led “in exile.” This concept is a kind of inverted antisemitism; it is an acceptance of the antisemitic premise that Jews are an alien element, that they do not belong in the countries in which they live, work and love.

Thus, American Jews have developed a separate Jewish identity, making distinctly “Jewish” contributions to American culture and history. The vibrancy and rich variety of American Jewish life has been the result of interaction, not with an abstract and purely pan-Jewish culture or history, but with the specific character of American society. The fact that the Jewish community has taken its place within the center of American bourgeois culture and values is precisely why a socialist critique, not a Zionist ideology, is the demand of the current historical moment.

This raises the question of the relationship between American Zionism and the Israeli government. Despite common goals, each partner has attempted to impose its own brand of Zionism on the other. During the mandate period, the prosperous American Zionist movement attempted to direct the economy of the yishuv along the lines of “private enterprise.” The Jews of Palestine, however, favored colonization in the form of collective agricultural settlements. Since the consolidation of the state, Israeli officials have employed the support of American Jews to gain leverage with the United States government. After the 1967 war, the interests of both the ruling elite in Israel and the American Jewish establishment have virtually merged. Each has managed to define the concerns of their respective communities in terms of Zionist imperatives. In Israel this has been done by identifying security with expansionism and in the United States by linking the prosperity of American Jews with the role of a “strong” Israel serving American interests in the Middle East.

Those Jews who challenge this dominant tendency in the relationship between the Israeli and American Jewish communities must develop an alternative one based on the real long-term needs of both. Jews on the left must express their critique of Israel in a way that distinguishes between unacceptable tenets of Zionism on the one hand, and the rights of Israeli Jews for self-determination on the other. And this critique can no longer be satisfied by the repeated assertions of the Israeli government that the country and its people face the threat of imminent destruction.

Jewish and other socialists concerned with Israel must encourage and support those struggling for a truly socialist movement in Israel. A comprehensive Israeli socialist movement in the 1980s will have to develop a national consciousness which is not inherently expansionist; a program of economic and social development which stresses equality and is not compromised by excessive pragmatism and bureaucratism; and a spiritual outlook which is able to withstand the pressures of religious fundamentalism.

Currently, the major task is to struggle for Palestinian-Israeli reconciliation. Military superiority has engendered a fierce arrogance among Israelis while subjugation has created immense resentment among Palestinians. If progress toward reconciliation is to be made, Israel must end its oppression of the Palestinian people and accept the legitimate right of the Palestinians for the own state on the West Bank and Gaza Strip. In turn, Palestinians must concede the existence of an Israeli-Jewish nation with its own legitimate rights. Beyond the nation-state solution, it is necessary that both peoples strive for mutual cooperation within the broader framework of a socialist Middle East federation.

Furthermore, Jewish socialists must take the lead in the effort to demystify Zionism. This political phenomenon has been and remains “overdetermined” -- it is burdened with all sorts of fanciful notions and wild associations. While some of its proponents regard Zionism as a sacred concept and a legitimate religious belief, some of its opponents view it as a malevolent force beyond history and rational understanding.

It is important to recognize that Zionism is neither merely a tool of western imperialism in the Middle East, as the crude anti-Zionists assert, nor simply the national liberation movement of the Jewish people, as Socialist-Zionist apologists maintain. And just as socialist anti-Zionists frequently fail to acknowledge the severely limited options faced by oppressed European Jews attracted to Zionism, so Socialist Zionists are unable to perceive the disastrous consequences of the Zionist belief in economic, social and cultural segregation as requirements for the rebirth of Jewish national life.

Zionism can only be demystified by viewing it for what it is – a political movement and ideology which arose from, and developed in, a specific historical context. It is neither a religious doctrine nor a demonic entity. In order to understand Zionism and critique it intelligently, we must analyze its history and nature with the critical conceptual framework of Marxist theory. Only then will we be in a position to refute the myriad distortions preferred by both sides of the conflict over Zionism.