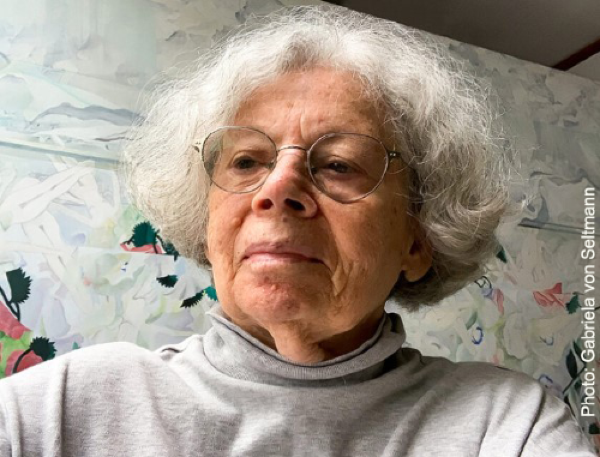

Irena Klepfisz: Perspective of a Lifelong Bundist

How do you resurrect a global movement that was nearly destroyed by genocide, fascism, and the wheels of time? And how do you continue that movement when so much has changed since its heyday? More than a century since the founding of the Bund in 1897, neo-Bundists today are facing a dramatically different world. The state of Israel is not only a fact but also receives wide support from the majority of Jews in the diaspora, as well as the governments of the United States and other Western nations. But a new generation of young Jews is gaining political consciousness in an age when Israel's crimes in the name of international “Jewish safety” are more visible than ever.

Last month, Der Spekter editor Josh Waletzky, 76, and New York City-based Bund member* Maddan E., 21, sat down with veteran activist and poet Irena Klepfisz, 83, to hear her perspective on the past, present and future of Bundist organizing.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Josh Waletzky [JW]: I'm Josh Waletzky, here representing Der Spekter, an online independent Bundist publication. I'm 76 years old, born a couple of weeks before Israel was, so I always know how long the state's been around. And I have had some connection with the Bund itself. In the 1970s, I was a member of the Yugntbund, the Youth Bund.

Irena Klepfisz [IK]: Was that with Jack and Danny Soyer?

JW: Yep. Jack Jacobs, Danny Soyer, Feygele Jacobs. Bobbi Zylberman — Getzoff, at the time — was in those circles and is now in Australia. Her husband is currently the President of the Melbourne Bund; their daughter is Vice President. And, incidentally, I recently learned that my grandfather was the first treasurer of the Bund in New York City.

Over the years, I've been active mostly in the Yiddish cultural sphere as a filmmaker and as a songwriter, a composer. My political activity has been in a Bundist direction, but not connected to the Bund, which more or less became moribund in New York City after the 1970s. I was active in housing organizing and in labor organizing in the editors union. And of course, since October 7th, but even going back to, I would say, Rabin's assassination for me was a turning point where I felt like, “Whoa!” I turned from being a non-Zionist, or alienated by Zionism for many reasons, to like, “No, no, no! Lo ze ha-derekh (This is not the path).”

Maddan E. [M]: Hello, I'm Maddan. I am a member* of the Jewish Labor Bund. I'm 21 years old. I've had very little time to organize or be involved in any real movements, but as long as I can remember, I have pushed against the part of me that was taught to believe in Israel and to believe in Zionism. My grandfather was a reporter who was very active in Israel, very soon after its inception, and went on to work with many leaders, and created a lot of propaganda as well as a lot of false information, which he used to support the state of Israel. And back when I was young and used to read his work, I would find small errors and be confused by them, bring them up to him. And he'd always push back very militantly. It's something that I've had to deal with a lot internally. Understanding that he was largely a mouthpiece for Zionism and one of the people spreading the movement is very hard, as I deeply respected him and his work for so much of my life. And part of the reason that I'm part of the Bund now and want to create a difference is because I want to atone for some of the mistakes he's made. I would consider a lot of my organizing to stem from that. I learned anti-Zionism first, socialism second, and would never look back.

IK: When did that happen?

M: I started noticing issues when I was around 10, and I used to write my grandfather long emails, saying, “I don't believe this is true. Is this a mistake?” But I hadn't organized my thoughts or known enough to write anything until I was around 13, for some school projects, and sending them to him, because we were very close and I thought he’d listen to my notes and fix mistakes. It was always very difficult for me to deal with this. And from there, our relationship kind of decreased in intensity until recently, when he passed. But it's been good for me to be a part of this and to really engross myself in an understanding of what this all means. I really feel like I now have a principled position that I can fully justify and explain and understand.

IK: I'm Irena Klepfisz, and I grew up thinking that to be Jewish, you had to be a Bundist. (laughs) That's all I knew. Everybody I grew up with — I would say at the beginning, especially, because they were very wary of American-born Jews — were survivors, Bundist activists. A lot of them were active in the Jewish resistance via the Bund. So I knew people like Vladka Meed [Jewish resistance fighter in Poland], and I knew Marek Edelman [a leader of the Warsaw Ghetto uprising]. Other people were less well-known, like Bolek Ellenbogen, and his family and his sister, who played an important part in my mother's and my survival during the war.

I came to the U.S. when I was eight and had my first real encounter with Jews other than Bundists. In Sweden, I went to school and was the only Jewish kid. There was no problem. I'm not sure I even knew I was Jewish, and I don't remember any references to the war when I was in Sweden, though I know that people were having yortsayts [memorial gatherings] and all of that, but I was sort of protected from that.In the United States, I encountered these other Jews. I grew up in the Amalgamated [a cooperative housing development in the Bronx, sponsored by the Amalgamated Clothing Workers Union]. And I remember my first time when I was in the park flying a kite with a friend. And she saw a star in the sky and said, "I have to go home." It was Friday, and the first star indicated the beginning of shabes, about which I had no clue. We were not religious in any way. We were not kosher. We didn't go to synagogue. And we were not anti-Zionists at that point, and Israel just hardly played any part in our existence.I just grew up with Israel in the periphery. So to me, politics was Bundists and Bundism. Bundism, of course, meant socialism. It meant Yiddish and Yiddish culture. And growing up in the Amalgamated was like living in a Bundist shtetl. There were Yiddish newspapers, a Workmen Circle Yiddish shule [pronounced “shu-leh,” (after-school) classes for secular Jewish children]. It was the biggest in the city. We had a hundred kids. Chaim Grade lived there, so you could bump into him on the street! You know, it was very, very different. So I was very shocked, for example, when, during Passover, Pesach, when I went to my public school to see girls with matzo sandwiches. We ate matzo, too, but we didn't give up bread. If you're going to have a sandwich, you used bread.

About Israel: One of the things that Bundists recognized was that there were Bundists in Israel, because a lot of survivors that had no choice, ended up in Israel. So in 1962-63, between college and graduate school, I went to Israel. So I saw Israel before the '67 War. And in fact, I worked on one of the kibbutzim that was attacked on October 7, Nir Oz. It was a brand new kibbutz, just five years old. Everybody was maybe 23, 24. They all served in the IDF. Nir Oz was really a military outpost at that time, which I didn't realize. There were around 40 very young kibbutzniks there. And it was right on the Gaza border.

This was a Hashomer Hatzair [left-wing Zionist] kibbutz. Before she met my father, my mother was a Zionist and the son of a childhood friend was in Nir Oz. So that's how I got to Nir Oz. Then I went to another Hashomer Hatzair kibbutz. And Abba Kovner [a leading member of the Jewish armed resistance movement in the Vilna Ghetto] was on that kibbutz. But he was away. So I never got to meet him. I also went to Lohamei HaGeta'ot and missed Antek Zuckerman and Zivia Lubetkin, who also were not there that day [both were leading figures in the armed Jewish resistance in the Warsaw Ghetto]. I just missed everybody who knew my father and who fought with him.

Though I liked and became attached to many people that I met there, I didn't really like Israel. I found Israeli attitudes towards survivors and the Holocaust terrible. I mean, they just thought we didn't resist. [IK's father, Michal Klepfisz (1913-1943), was a Bundist and an active member of the Jewish armed resistance fighting the German Nazis in the Warsaw Ghetto.] I didn't like their attitude towards other Jews. I did not like how the Israelis said that Jews were sheep. They wanted to disassociate themselves from the 6 million. The Israelis were “the new Jews” and all that nonsense. And this was maybe a year or two before the Eichmann trial. The Eichmann trial turned things around in Israel a lot. Abba Kovner and other survivors testified. There was more information about resistance in ghettos and camps. Israelis began to understand more about what had happened. But from then on, I was just sour on it. But at the time, I was also totally nonpolitical. I did march in the '60s in Chicago against the war and once for civil rights in Skokie, outside of Chicago. That was it. I remained apolitical and uninterested in Israel. I was interested in the United States, but I wasn't engaged until I came out. And when I came out — when it becomes that immediately personal — you become active. I came out over the issue of homophobia, an issue that my parents and the Bund had never thought about. "Lesbians" and "gays" weren't even in their vocabulary. Their doikayt was quite different from my doikayt.

After I became more known through my poetry — and partly because of my background and the war, because I had this connection to Yiddish culture — somehow America's craziness around “the authentic Jew” landed on me. So within the movement, people started looking to me for answers. And when I entered the movement, I entered it in the left. People describe the movement as very monolithic. It wasn't. There were many arguments, for example: Is racism a feminist issue? Do we have to address class? That kind of thing. And anti-Zionist issues were being discussed. And women started asking: “Oh, Irena, what's the answer?” And I didn't know. I was uneducated. But I was really, really pushed.

We formed a lesbian group called Di vilde khayes [The Wild Beasts] to try to address this issue. But we really were unprepared. We were so ignorant. I think we formed it like in '81 or '82, and by '82 Israel had just invaded Lebanon, and there was the Sabra and Shatila massacre. And so, at that point, I started becoming more serious. And Melanie Kaye/Kantrowitz and I decided to edit a Jewish feminist secular anthology. Susanna Heschel had published “On Being a Jewish Feminist.” But it was focused on observance and rituals. And Melanie and I are both secular and felt it didn't speak to us. We wanted a more comprehensive anthology, and we wanted gays in it. And we recognized multiculturalism within the Jewish community. And we also wanted Israeli Jewish women represented. So we decided to go to Israel to talk to Jewish and lesbian feminists. And this is like 1985. So that was my first trip back. And it was a different country than what I had seen in '63. Totally different. And we connected with a lot of lesbians and feminists and talked to very prominent figures like Alice Shalvi and Galia Golan. Galia Golan had started Peace Now. She also initiated the first women’s studies department at Hebrew University. For me, this trip was a real education. I saw the West Bank for the first time, and I was shocked. Because my whole sense of history was based on the use of the word "settler." And I had seen a kind of "settlement" in Nir Oz in 1963 — which was totally impoverished. But when I got to the West Bank and saw these housing complexes, I said, “These are settlers? Settlements? These are like monuments for the next 300 years!” So it was a shock. And of course, one of the things that came up was my socialist beliefs and how I was raised. And I was kind of remembering my Bundist socialist upbringing. I didn't really have a grasp of Bundist history. I knew it anecdotally, and I knew it only in its broadest principles. So I started learning and reading and teaching and feeling very comfortable with it, but realizing it needed "updating" to my doikayt and to the U.S. to include issues like homophobia, racism, etc. And at the same time, I started learning about the Bund's struggles with Zionists before the war and realizing that everything that the Bundists had predicted was happening.

I always thought of myself as a Bundist, even though there was no Bund, really. There's a lot of nostalgia about the Bund, and more people are beginning to appreciate it.

The Gaza genocide and the future of the Jewish left

JW: Turning to the present: Has the war in Gaza made a real inflection point in Jewish history?

IK: That's what they talked about today, actually [referring to a conversation with Rashid Khalidi and David Myers hosted by Peter Beinart earlier in the day this conversation took place]. What is this historical moment? Everybody recognizes it's a historical moment. Nobody knows where it's going.

JW: Right. But it's going somewhere else than where it's been going.

IK: Maybe. I mean, we want it to go in a different way.

M: If I can pose that question, actually. Where do you think we should be taking it? If we have control over that narrative, where should we lead with it?

IK: It's a complicated question. Do you mean immediately in response to the war? Or, in the long term? One way to answer is to ask: What do you think is missing?

What is it that's missing that needs to be created and that the Bund could address? I could list a whole string of things that are missing. First of all — long term: I raised this at the conference — Jewish education is a mess. And I'm not talking about Hasidim; that's a whole other story. But in these other Jewish schools. I was shocked that one of my friend's sons in such a school was told to write letters to “their soldiers in the IDF.” What are they teaching there? At Barnard, I encountered students who had Jewish educations but who didn't know the word “occupation.”

I think teach-ins are great — especially for addressing immediate issues. One of the things I know that they have on these encampments is teach-ins. And you should be able to do teach-ins outside of the encampments, in some way, so that people are getting historical information. What's missing is, I think, accessible, easily-read literature that outlines some history that you can give out at protests or at meetings. I think that's critical. It's one of the things that's just not out there.

There's one function that's very obvious for short term issues: you want to pressure for immediate change. But I think one of the things that you have to do is identify who you're talking to. Who do you think you can reach? And what is it exactly that you want to say? And I don't think that's very easy to formulate.

One of the things that I found that's very useful is to have what used to be called in the women's movement, “CR groups,” consciousness-raising groups. And you say, “What is Zionism?” Start with the simple one. “What does Zionism mean?” Or, “How are you Jewish? What's a Jewish activity? What is antisemitism?” And out of those kinds of conversations emerge really good ideas about people's strengths, what they believe, what they're missing, what they want, what they're afraid of. And also, it becomes a way of finding out who you should be addressing and also how you should address them. We need an educated, up-to-date membership.

David Myers today said, “Ask the question, ‘What does this word mean to you?’ or, ‘What does this idea mean to you?’” They were talking about "from the river to the sea." And it was interesting that David Myers said there was a recent study done, and that 66% of Jewish students questioned considered this slogan to mean annihilating Jews in Israel. 86% of Muslim students didn't see it that way. They just saw it as freeing Palestinians. Two very different meanings of the same phrase. That kind of education seems vital. Because everybody is walking around totally ignorant of history. The Bund was always strong on education and on literacy. Very book-minded. At our Third Seders, or our seders, every child had to find the afikoymen. Everyone would wait until the last child found it. And then every child got an age-appropriate book.

JW: [laughs] zeyer bundish. (very Bund-like)

IK: And that's one of the things I really love about the Bund, is that it's very open to a wider world. It's focused on Jews and committed to improving Jewish life, but it also wants the Jew to be part of veltlekhkayt (worldishness), to be part of the larger world, to be in touch and engaged with the larger world and its challenges, and not to feel a stranger in it.At your meetings, you set your own priorities. And maybe look critically — not from the point of view of tearing down — but looking at what other groups and institutions are doing: what you like about them, and what you think they're missing or failing at. What need could you address?

I think it's important to emphasize that Bundists weren't just socialists focused on economics and class systems or only on anti-Zionism. They really wanted to improve all aspects of life. And it's true that they had sports organizations because Jews were locked out [of Polish sports organizations]. But it's also true that, even now, people have a need to create their own communities. Somebody at the conference [referencing the symposium on “The Jewish Left” organized by Boston University's CURA on May 3, where IK was a speaker and JW attended] said, “People like to belong.” They want to belong to a kind of community that they can share, not just the immediate issue you're protesting for or working towards, but who can share a meal together, who can share theater together. And the Bund was amazing about that.

My father is always described as a Bundist. Well, you know, he was very active in Morgnshtern. Morgnshtern was the Bund's sports organization! (laughs) That's what he loved. He was a real sportsman. So the Bund had a variety of organizations, including SKIF [Sotsialistishe Kinder Fareyn — Socialist Children's Association]. Tsukunft the youth movement. They organized schools and libraries and the Medem Sanatorium, which was a very famous sanatorium that was created mainly for poor children who had tuberculosis and who came to be cured for long periods of time. But what was special about the Medem Sanatorium was that it was run by the kids. The kids were being taught to practice their socialist principles. But all these were political institutions. We need institutions like that. And we don't have them.

M: Yes.

IK: We need institutions, educational institutions that teach the parents as well as the children. We have lots of opportunities to learn about the classical Yiddish writers like Sholem Aleichem and Peretz. But there is so much more to be offered. Again — teaching the parents as well as the children. No one is doing that in a focused and systematic way. But that's the kind of thing that the Bund could offer. Provide a cultural institution that is rooted in Bundist politics and that's not afraid of being openly socialist and political. But, of course, a lot of this requires time.

JW: Just to add on here, I will be teaching this summer in July: five two-hour sessions on Zoom for the Workers Circle. I'm going to teach songs written by people associated with the Bund. The political songs, anti-Zionist songs, but lots of other songs, with texts by Ansky, Leivick, even Gebirtig, who was a Bundist.

IK: Yes, he was a Bundist. That song about Avreml is rooted in Bundist ideology. [Avreml der marvikher (Avreml the Pickpocket)] Avreml knows that if people had cared for him, he wouldn't have been a crook. He's very, very proud of being a thief. He says he's the best. And he's careful about who he pinches: only the wealthy. And yet in the last stanza: he laments that if he hadn't been brought up in the street —

JW: His matseyve, his tombstone —

IK: — would be very different. He would be remembered for his decency. It's not nature, it's all nurture. It's a wonderful song. I love that. Because it's so compact.

JW: He was a great songwriter!

Breaking down political barriers

M: Speaking more about nature and nurture, I think a lot of the issues we're facing now with educating youth — and this is becoming less of an issue as materials on the internet become easier to use — but a very large problem is that the nurture in America is so absolutely ingrained in liberalism and capitalism, that there's almost the Mark Fisher: You can't imagine a world after it [referring to Mark Fisher's influential Capital Realism: Is There No Alternative? (2009). What do you think is the best way to start working toward breaking down those preconceived notions? Stuff that people don't even understand is political, but is.

IK: There's no magic answer for that. One thing that, unfortunately, we all have to get resigned to is that nothing happens quickly. Especially shifts in consciousness. As I said before, there's the immediate and the long-term. For the long-term, things happen very slowly. But what I would suggest is that you start building a committed group of people. It can be small. I used to have students who used to say, “I want to do this and this, but there's only two of us that want to do it.” And I would say to them, “Do it!” Because I've been involved in projects that began with just a handful of people. One of the most influential magazines during the feminist Second Wave for like 30 years was Conditions magazine. Four of us started it. Nobody had heard of us before we began. It was never, in terms of numbers, huge. I don't think we printed more than 1,500 copies per issue — and that was for something special. And we came out very irregularly. But it was incredibly influential, with major writers contributing.

[With] the Bund, in 1897, 12 people met in an attic in Vilna, and 30 years later, hundreds of thousands identified as Bundists. And Black Lives Matter, three African American women started it.So if you get together a small number of really committed people and try to figure out how each of you can reach a certain number of other people to achieve certain goals you can be very effective.

Be clear about your objectives: What do you want to achieve there? Do you want visibility? Do you want to provide information? Have a dialogue? If you're going to protest, adapt your message. Maybe you shouldn't use the word “genocide” in certain places, because that immediately turns some people away. Maybe you can just say instead, "it's terrible."

For a number of years, JWCEO [Jewish Women’s Committee to End the Occupation of the West Bank and Gaza] stood in front of Zabar's on the Upper West Side [the iconic Manhattan Jewish appetizing store]. We met a lot of Jews; they all wanted to talk. It wasn't a silent vigil but an invitation to discussion. Have material to give out and see what happens. Maybe you'll get people to join you. Maybe you'll get a lot of hostility, which I'm sure you will. Simultaneously, you may join the big demonstrations and do these other things separately while trying to build up your own membership.

M: For me, I lead the Instagram account with a couple of khaveyrim: @nycbund. And on the anniversary of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, we posted a description of the Bund’s involvement in the struggle against the Nazi forces, and how much of it reflects what we see in Gaza now. The complete destruction of an entire ghetto. And how we can't let that repeat. For things like that, I think that these mediums can be very helpful in just getting the image and the idea of it out there. And have people react emotionally to it. But when it comes to getting people involved in the movement, we need writing. And we need people who learn.

IK: Well, that's why organizing for either a discussion or a cultural event is useful. For example, the songs Josh wants to teach — have an event in which you sing them here in New York and offer them to everybody. Come hear a Josh concert, or whoever you want to work with. And make it a Bund event. And people will come. You offer literature or history lectures and maybe people sign up. I think it's the personal interactions, the contact with people that engages people to join.

M: Very much.

IK: Or offer something that makes the contact personal.

JW: I underscore that because there's so much that gets communicated in person. I was thinking about your appearance at the BU conference [the May 3 CURA symposium on “The Jewish Left”]. You were able to hold that room with physical presence as much as with what you said.

IK: But you know what I was aware of during that presentation, and I really became aware of it? The poetry. It changed the energy in the room.

JW: Absolutely.

IK: After all those speeches, the poetry. It was political and had political points to make and was just as serious. But reading a poem, singing a song — they change the atmosphere. And I think that people are responsive to that.

JW: Right.

IK: Or have a reading with Palestinian and Jewish writers and poets. Or just have a reading of people's favorite poetry or poets. Those would be events that people would rush to.

M: I've been pushing for starting up another reading circle, within the New York City division specifically.

IK: That sounds great. I've helped facilitate reading groups and Yiddish materials in translation, and English texts. And that could be done both in person and also with Zoom, where you can actually get more people. And those actually work better than I thought. It's not the same as being in person. But that's the kind of thing that I think other people aren't doing and could draw people.

M: Yes.

JW: Yiddish cultural material is vital. But even most anti-Zionists or people that question Israelism as the center of Jewish identity are completely ignorant of all the Jewish and Yiddish cultural materials from the last 150 years. But even before that. They go back to Rashi and that's where that ends. And then they skip forward, and they go to people that wrote in German or French or English.

IK: They don't know. It's been erased … like April 19th [the date of the beginning of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, observed as a solemn day of remembrance by Bundists, in particular, at a long-standing ceremony in New York City's Riverside Park at the site of a municipal Holocaust memorial]. Most people don't have any idea.

There are so many things that I feel are missing from our present world that you could address. And the big one, as we already said, is called: institutions — that are willing to be political, that are not dependent on donors.

Some are saying the elite universities are collapsing and the Gaza-Israeli war seems like almost the last straw because they've been under siege from the right for months. This is what DeSantis is doing in Florida, just dismantling all education. All schools are getting rid of DEI [Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion practices and policy].

M: The whole war against critical race theory.

IK: I was horrified about what happened at Dartmouth when everything started falling apart there. Everybody had been interviewing Dartmouth professors about the fact that they didn't have any disruptions there because they had all these open discussions with their students and so on. Yet five days ago, there was an encampment. The administration called the police and a riot division for backup. When the police started coming, the former head of Jewish Studies and a whole group of teachers formed a line in front of the students to protect them. And she was grabbed and pulled along on the ground and smashed and so on.

My colleague & friend, the great labor historian Prof. Annelise Orleck. Annelise is out & ok, but was told that a condition of her release is being banned from campus, despite currently teaching two courses. https://t.co/VQp8UAqu7W

— Jeff Sharlet (@JeffSharlet) May 2, 2024

M: I know you're a CCNY graduate [City College of New York (CCNY) is the oldest of 25 colleges that make up the City University of New York (CUNY)]. At the CUNY encampment at CCNY, that was a very big issue. I was there the day that it got swept up. The police came. The current head of CCNY didn't engage in negotiations whatsoever. He never showed up. He sent an email and said that he had been trying his hardest and no one was listening, when in reality he had sent two people to go and just say “No” to whatever was said. And that night, when he called the police, I was there just before and they had a little group of kids that were just reading regular books. Nothing like propaganda shtick.

IK: Wasn't that the same night as Columbia? Because the reporters were running back and forth.

M: I left there just before the police got called. My girlfriend was cold, so we went home, and on the train home, I kept having to wait between stations to get cellular connection so I could stay updated on notifications about the brutality. I had friends who were pepper-sprayed, some students were beaten, others arrested. And the immediate response from CUNY when pushed on this, and the protests that have ensued since, was to introduce a new resolution to introduce a $4 million contract with a security corporation that is directly involved with Israel. And it's beyond insulting. Insulting is the least I can say about it. It's $600,000 a week, plus the $4 million contract. They'll be hiring 24/7 security forces. They say a hundred security personnel.

JW: That, they have money for.

M: Not for the PSC [the union which represents faculty and staff at CUNY] negotiations when they were discussing union activity with teachers. Not for the students, not for divestment, but for the cops to attack more students.

IK: Khalidi said that the Columbia campus is now surrounded by New York City police and Columbia's own private police. He said it's an armed encampment, that there was a period where he couldn't even get on campus, even as a teacher. It's just really disturbing.

The future of Jewish organizing for Palestine

M: So I guess that can lead to another question. Where do you see the encampments leading? Do you think that we continue them and push and go for a citywide action? Or do you think that as the school year ends, we just move on to different tactics?

IK: Well, I don't know … during the summer when people aren't around and probably not that many students are, right? I mean, there's usually some students always, it doesn't shut down.

You could use this time to refine your message and try to build up your resources over the summer and not be so visibly active all the time. I don't know what other people are going to be doing, but I know it's still going to be a problem in September.

M: Yeah, of course.

IK: If you do stop, it is a good time to test things. Go to a corner somewhere with some kind of sign and see what happens. See who comes, what they want to talk about, what they don't want to talk about. If they criticize your sign, let them explain why. Make it into a kind of learning experience for yourselves as well. It's a hard thing to do, because, as I learned, Jews can be horrible to each other.

M: Yes.

IK: I had Jews say to me, “I wish you had died in Auschwitz.” Thank you. (laughter) I'm glad you shared that. But still, it was educational for me because I just never met Jews like that. And it's good to know. But you also meet other people that are on the fence or that are confused.

When we began JWCEO [Jewish Women's Committee to End the Occupation of the West Bank and Gaza], we went in front of the Conference of Presidents [of Major American Jewish Organizations] which was on some top floor in a tall building. We were on the sidewalk. It was stupid. (laughs) We weren't talking to anybody. So you have to find the spot. If there's a favorite deli or cafe somewhere. Like in the Bronx: Liebman's [Deli]. That'd be interesting. What's going on up in the Bronx? That whole Jewish enclave and The Amalgamated [Housing Cooperative] — those are mostly secular Jews up there. What are they thinking? That's what I would do. I'd build up resources, try to create maybe pockets in departments and have people in charge and responsible that they have to answer to some committee. Don't make it too bureaucratic because that always works against you.

M: We have quite a few people to reach out to. say,Outlive Them is a big one in New York City. They're a group of Jews that walk around and go to protests to defend and help out as much as they can. There's other groups that I won't mention, but just a lot of people who we can and will reach out to. I think it is a good idea and a good time to start building up the institutions we need. Right now, there's so little unity among the groups that are doing these things. And there needs to be some sort of unity if we expect this to become bigger.

IK: Right. The Bund could be really good at that.

The misuse of “Jewish safety” and “antisemitism”

JW: I think one of the attempts to turn Jews — and others — against the pro-Palestinian protests is this notion that any criticism of Israel is antisemitic. Just a few days ago, Biden came out with a statement claiming that there’s a “ferocious surge of antisemitism” in the United States, referring to what’s happening on American campuses.

IK: I have a certain amount of resistance to believing charges about antisemitism because it’s been so misused. And I certainly don't think feeling uncomfortable at a university is a reason to stop protests.

M: I can speak to my experience. I've been to all the encampments, maybe missing one or two, and there was not a single moment where I felt uncomfortable whatsoever.

IK: But, you know, it's not bad to be uncomfortable!

M: Of course.

IK: I taught classes in which I had observant Jewish women who'd had Jewish educations, and I was teaching a novel about the difficulties faced by a girl growing up in a Hasidic family. And these young women were very uncomfortable with it. Some of them had to listen to the other students promoting feminist perspectives and how they were disturbed by some of the Jewish customs. And not only were these observant women practicing some of these customs, but they were also going back to homes where these customs were required. And I found these observant women to be very brave, very gutsy. And I know they were uncomfortable. But the materials they were reading weren't antisemitic.

But there were students who thought: We shouldn't be reading this. We shouldn't be promoting this literature because it feeds antisemitism. And we'd discuss that. I told them that I don't think that what we Jews read should be controlled by antisemites, and antisemites shouldn't be controlling what we write.

You know that old question, “Is it good for the Jews or is it bad for Jews?” That doesn't work. There are many observant students and they walk into classes on religion that discuss the existence of God and yet these students’ whole lives are all about God. They're uncomfortable.

M: And that's part of learning.

IK: That's part of learning. “I feel uncomfortable.” “I feel unsafe.” Are you actually unsafe or you just feeling unsafe? I mean, anybody can say, “I feel unsafe.” Half the women walking on campuses at night feel unsafe. And they actually are unsafe. Of course it's important to address the Jewish feelings of fear because they are real, but also to recognize that they don't automatically prove the intent or the existence of an actual physical threat.

M: And they aren't the ones that are listened to. It's the fringe Zionists who are saying they're unsafe that are listened to.

IK: But if you feel unsafe because of a certain activity, are you really unsafe? Is somebody going to be hurt? — Is there a history of violence? These questions need to be answered.

JW: Early in the pandemic, there was a video — I'm sure there were many like this — but there was some big box store and a short little old grandma was pushing her cart, wearing a mask. And some big, burly guy rushed up to her, said, “You're being aggressive.” She may have asked him to put on a mask. And the big guy tells her, “I don't feel safe around you.”

IK: These encampments have been perfect for the right-wing to use against these universities. They were after the universities to begin with, and they found the perfect hammer. They're suddenly upset about antisemitism. It's ridiculous.

M: It's, of course, the same party, the very same people, who have spread antisemitic lies for the entirety of their stay in Congress.

We could talk about the hypocrisy for a thousand years. People don't care. Even at the protest, the people holding the Israeli flags who are going up to people and saying that we should have died in the gas chambers and whatever else. It's the same. That's not antisemitism? The antisemitism is the people, largely Jewish people, that are standing up against it? Ridiculous. It makes no sense.

IK: We mentioned before trying to define terms. I can't remember a time when we've had to be so careful about our vocabulary and how we speak and when we use the same words if we understand them in the same way. Zionism, antisemitism, etc.

A friend of mine recently wrote me that she was talking with someone from a local protest group (and I know this is not prevalent, but it's a good example) about Hamas, or their discomfort about how to talk about Hamas. And at some point this person said, “Well, you know, the Warsaw Ghetto resistance fighters, they were terrorists too.” (laughs) But you can't twist history or the meaning of words like "terrorist" for your own political purposes. It's absurd.

Khalidi said [again referencing the Khalidi-Myers-Beinart conversation] that there was not a single liberation movement that succeeded that didn't use terrorist and violent tactics. And he named them: the ANC, IRA, Algeria and the French ... and he said, that's not to excuse or make easy what happened on October 7th. But it was an interesting point. And I would add: especially when all peaceful methods are being dismissed.They don't want BDS and they don't want all other nonviolent actions. But then they get upset when people get violent. And you should be upset. It's not that you shouldn't be. But it remains difficult to talk about.

JW (to M): So, do you have any other directions you want to get to?

Beyond ‘ceasefire’

M: I'd say that a big issue that I've noticed is that there is a lot of hesitancy to start accepting further-left political dialogue — even among groups that are organizing for Palestine — though recently I've noticed some people advocating for socialist revolution and change who are not afraid of the words. But even then, what I see online at least is a very watered-down version of the dialogue that's being used by these groups.In trying to build up actual institutions and trying to create the dialogue, is there a way to advertise to people that we don't think would use that dialogue — issues about class war and issues about needing to fight for revolution, outside of just calling for a ceasefire in Gaza. Saying that they need to accept resistance movements and start pushing for independence for Gaza. I agree with those kinds of words, but they're not so easily understandable or widely accepted. When walking that line, is there a way for us — aside from just analyzing our audience and trying to understand who we're talking to...

IK: I'm not sure I can really answer that. I think it's something that you're going to have to feel out. I don't know of a formula and there may be one that I don't know about.

It's always difficult to connect or combine different issues. I experienced that tension in the women's movement. For example, many women at first said that “Racism isn't a feminist issue. It's not our issue. We shouldn't mix it all up. The socialist or class issues are not really feminist issues. We're interested in women." It's difficult to promote while trying not to alienate. I know at the time, some of us were convinced that racism was a part of the feminist agenda and that it would be wrong not to address it, especially if you want women of color who are experiencing daily racism in their lives to join you. How could it not be?

The same thing happened around homophobia — initially the Second Wave was horribly homophobic. The early feminists didn't want lesbians to come out because they were already being accused of being dykes. In the lesbian movement we also had tensions around racism, antisemitism and class issues.

In Israel, for example, Alice Shalvi headed an organization, Israeli Women's Network. And she included women from the settlements in the West Bank. There were big arguments about that. Should these women be included? And Alice said, “They're women. I'm not going to cut them out.” There were other people who said, “No, they're not our allies.” And she persisted and there were people who fought with her about that.

I think you have to figure out: what event you're at, who's going be there, whether you're going to shoot yourself in the foot. At the same time, you don't want to be speaking from both corners of your mouth, saying one thing to one group and another one to another. You should always provide a complete set of Bund principles. You might stress or address one issue, but in the end, most issues are interconnected. And of course, it's vital for the Bund to form alliances with other groups.

It's important to remember people do change their minds. My favorite example is Melanie's and my interview in '85 with Galia Golan. She was adamant: “There's no connection between my work with Peace Now and my work on Women's Studies. They address completely unrelated issues. Peace is here; women are there.” Two years later, when “The Tribe of Dina” was being reissued, we wanted to update the Israeli interviews and Galia Galon wrote: “You know, I thought about your question about connections; and I've decided that they're connected, women and peace are connected."

But like I say, you show yourself as a multi-issue organization ... [New Jewish] Agenda did that. It had task forces on gays, on Israel and the Middle East, on racism and antisemitism and more. If you're a multi-issue organization, your literature should say that in a very succinct way so that the people know right away what the Bund stands for.

M: We've even had that issue with the label of anti-Zionism — even some people in the Bund were saying that they weren't comfortable calling themselves “anti-Zionist” and wanted to be called “non-Zionist” or just avoid it. It's a difficult discussion to have within groups like ours.

IK: You have to decide what your core principles are. And they should be visible everywhere.

M: Right now we have the three pillars, which are Jewishness, doikayt, and socialism. And those have led us well so far. And we'll add to that. We have a lot more to do.

JW: So any other last licks?

Book recommendations

M: Do you have book recommendations for the reading group or for anything we want to do in the future?

IK: It depends... about Israel-Palestine? The Bund? Are you interested in literature? In politics? History? Poetry?.And whose? Jewish? Israeli Jewish or Yiddish Jewish? Israeli-Palestinian etc.?

M: I have Khalidi's “The Hundred Years' War on Palestine.” One of my favorites.

IK: “In geveb” [an open-access digital forum of Yiddish studies] has a lot of material in translation. “In geveb” is really a good resource, actually, for a lot of stuff — for historical and literary material. You should look at it. They had a whole article about Yiddish literature that addressed racism. Poetry about racism, about Gaza in Yiddish and in English. Also everything that they do is always bilingual. But just let me just say this about Yiddish. It's not the only Jewish language. So, I mean, are you addressing the language issue at all?

M: Not head on, but we have spoken about it in the group.

IK: The Bund of Poland didn't have many Sephardic Jews. During peysakh we sang the song Zog, maran (“Tell Me, Marrano”), but we sang it in Yiddish. (laughs). Today there are rabbis of color, Jews of color. So if you want to bring them in, Yiddish and Ashkenazi culture can't be your sole focus. So it's something to think about.

M: As of now, I'm working with the Ideology Group on a working definition for Jewishness. Right now we're using the word “constellation.” Jewishness is a constellation of beliefs.

IK: And cultures. You need people involved who are from these communities and they need to be an integral part of your organization, not just a task force. Your commitment can't be theoretical. You should institutionalize your principles.

Original interview recorded on May 10, 2024.

Irena Klepfisz' most recent publication is "Her Birth and Later Years: New and Collected Poems, 1971-2021."

* The International Jewish Labor Bund is in the process of formation and has not yet officially formed an organization, elected leadership, or established membership guidelines. As such, “Bund member” is loosely defined as being part of the organizing committee