“A Wound Opened Between Realities”: an interview with Sarah Ema Friedland, co-director of “Lyd”

Director Sarah Ema Friedland discusses imagining a future of collective liberation in Palestine through speculative fiction.

In the award-winning 2023 sci-fi documentary “Lyd,” co-creators Sarah Ema Friedland and Rami Younis frame the year 1948 as a moment that ruptured reality.

The film, narrated by the city of Lyd itself (“I used to be very beautiful. I used to be very famous. People from all over the world used to come and visit me”) — presents two realities: One, an alternate reality told in vibrant, colorful animation in which Lyd remained a great city that connected Palestine to the world. The other reality is the one we live in today, and zeroes in on a massacre at a mosque during the 1948 Nakba. We hear from a Palestinian man who was just 12 years old when he was ordered to remove decomposing bodies of men, women and children from the mosque. We also hear from Israeli soldiers who committed the massacre, who justified their actions, denied that innocent civilians were inside — one expresses shock and regret at his own actions, which reminded him of what Jews themselves faced in exile.

It’s another kind of dual reality, though this one exists in our own universe.

Last month, "Der Spekter" editors Josh Waletzky and Alex Lantsberg spoke with co-creator Sara Ema Friedland to explore the story behind the film. Just four weeks after we had this conversation, the Israeli police in Jaffa banned a local cinema from screening the film, acting on a request from Israel's Minister of Culture, who complained that "those behind the film support boycotting Israel." Elsewhere, it has been hailed on the international film festival circuit and lauded as "a masterful blend of historical documentation and speculative fiction." We hope you enjoy this enlightening conversation, and find a screening of Lyd near you.

Josh Waletzky [JW]: I want to start by expressing great admiration for the film that you and Rami made. It's just extraordinary. I think the dimension of imagination that you added into the documentary form was a brilliant and desperately needed dimension. Not to say that a lot of recent documentaries which address the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and horror are not necessary and valuable, especially for the North American audience. (The Bund seeks to speak to a worldwide audience, but the great majority of our adherents are in the U.S. and Canada.) Some recent documentaries like “The Blue Box,” “Israelism,” and a number of others trace the course of individuals starting from a Zionist upbringing to their disillusionment with that. But “Lyd” is a whole different thing, and such a welcome addition to the voices now being heard.

So, I want to start by asking for a bit of the film's biography. Jeyn Levison [JW’s partner and a US-based cultural organizer and activist] and I met you when you were in an early stage of working on the film. Could you give us a précis of the film's biography?

Sarah Ema Friedland [SEF]: First of all, thank you so much for having me. I'm just thrilled to be in conversation with you. I am — I don't know if “fan” is the right word, but I feel a deep connection to the Bund. My family were not Bundists, but I still consider myself a child of the Bund in philosophy and orientation.

This film started in 2015, and it is a co-directed project between myself and Rami Younis. Rami, who's not here with us today, has been an equal partner since the beginning. He is a Palestinian citizen of Israel from the city of Lyd. Lyd is his hometown. Many of the people in the film are people that Rami has known his whole life. And I think, you know, because this is a film that is made by a Palestinian from the place that the film depicts, and a Jewish American, its orientation, the position it's speaking from, the way it's speaking, is naturally very different from the projects that you mentioned.

In 2015, I read an article that was excerpted from Ari Shavit’s book "My Promised Land: The Triumph and Tragedy of Israel.” I was raised Reform Jewish in a pretty typical Reform Jewish way, and had never heard anything about the Nakba. And so when I read this article, which is very much about what happened in Lyd, it really blew my mind and kind of reoriented my whole view. The Palmach [an elite force of the Haganah] were my dad’s heroes. And our film goes deep into how the Palmach committed a massacre in Lyd. And so for me, reading about this was really intense. From the beginning Shavit positions the Nakba and the specific case of it in Lyd as a necessary evil. And I felt like, how could that be? I can't accept that. I can't accept that this is a necessary evil. And so our film really goes much further beyond that.

"[The Nakba is] a continuous tragedy, a catastrophe without borders in space or limits in time." – Elias Khoury

When I read about this, there was an opportunity to take part in this Jewish residency (which is where I ended up meeting Josh and Jeyn). And so I pitched this to the residency, and I was really surprised that I got it. And then I was like, oh shit, now I'm going to have to do it. And as often happens, I was not, at that moment, qualified to make this film by myself. I don't have any understanding of this. Really, I need a partner. And so Jeyn actually put me in touch with somebody who put me in touch with Rami.

Rami is an incredible, brilliant, amazing human being. He is a writer for +972 Magazine and was one of the founders of its sister site in Hebrew, "Local Call." He has been a very outspoken critic of Israel from the inside, from the perspective of a Palestinian citizen of Israel. He was an aide to one of the Palestinian members of the Knesset, Haneen Zaobi. So he's somebody who's a real kind of macher in the Palestinian citizens of Israel's political and artistic scene. And I was really thrilled to be able to work with him. We just really hit off.

So we started working on the film. And originally, partly because Rami comes from the world of journalism and I come from the world of documentary film, we were making a more straightforward journalistic film that was looking at the Nakba that happened in Lyd in 1948, the massacre and expulsion of Palestinians from the city of Lyd. But we always wanted to see it as a moment that has never stopped – the ongoing Nakba.

And I want to take a moment here to remember Elias Khoury, who died yesterday, who was a brilliant Lebanese writer, novelist, and literary critic. He has a quote that was really influential for both of us, and in particular for me, which is: "[The Nakba is] a continuous tragedy, a catastrophe without borders in space or limits in time." That, for us, was really pivotal in our understanding, because we wanted to show the Nakba as an ongoing process that continues today.

That was the idea of the film: to start in 1948 then to follow some of the refugees who had been expelled from Lyd and their descendants. And then also to come back to present-day Lyd to show how the apartheid system functions within Lyd. And we did all of that. But as we were making the film, and particularly when we were invited to pitch the film as part of the first-ever Palestine delegation to the Cannes Film Festival in 2018 through the Palestine Film Institute, we realized that we were making a film that neither of us would want to watch. It was way too tragic. It felt like it was only re-victimizing in that tragedy.

And so we were like, we need to rethink this. Now, I'm a big fan of sci-fi fantasy literature, and Rami loves sci-fi fantasy TV and movies. And so we thought this could be the vocabulary that makes sense for this film. Let's use this long tradition of world-making and rethinking political imaginaries that sci-fi fantasy has given us, like Afrofuturism and so many other kinds of ways of thinking with that vocabulary. Let's use that to imagine an alternate reality where the Nakba never happened, and what would that be like for the people in our film? What would that be like for the city of Lyd? And what would have needed to happen in the past to make that the reality of the present?

So in the film, in between this journalistic look at the Nakba and its continuation, we have these interruptions, these fantastical animated scenes, that do just that: imagine a world where the Nakba never happened. And we collaborated with a fantastic animation company in Egypt called Samaka, and they built that world with us. They're just incredible.

Another thing about that alternate reality is that a lot of it was a collaborative effort with our participants. A lot of what we originally recorded with them in their interviews makes it into the alternate reality. For example, one of our characters is Jihad Baba, who lives in Balata, a refugee camp in the West Bank. He has a line from his interview where he says, "If it weren't for the occupation, I would've liked to have become a lawyer, but it wasn't possible." And so then, in the alternate reality, we make him a law student in George Habash University coming out of the Hannah Arendt Lecture Hall.

Unfortunately, two of the people in the film died before the film was completed, but most of the participants of the film voiced their own animated avatars. So they also had the opportunity to review the script that Rami and I wrote and to add things or subtract things.

Alternate Histories

Alex Lantsberg [AL]: Could you talk more about that alternate reality/fantasy aspect? I really loved that. And I think when you were talking about how you had made a film that you and probably nobody else would have wanted to see, just because it would have been so just bleak, that alternate reality really does change the overall tone. I know you said that you're a fan of science fiction and speculative fiction, and you said that you had been working on this since 2015. The animated sequences in your film remind me of the science fiction device in the screen adaptation of "The Man in the High Castle,” of these sorts of views and punctuated glimmers of another reality as inspirations for action in this place.

SEF: Yes, I have read “The Man in the High Castle,” and I've also watched the TV show. I don't necessarily think of it as a main influence, but it's probably there in my psyche for sure, and I do really like the way that "The Man in the High Castle" TV show goes back and forth between realities. I'm sure that was part of my creative influence. Great reference. I love Philip K. Dick.

JW: What would you say were the things that most influenced the direction that the film took as you and Rami worked forward on it?

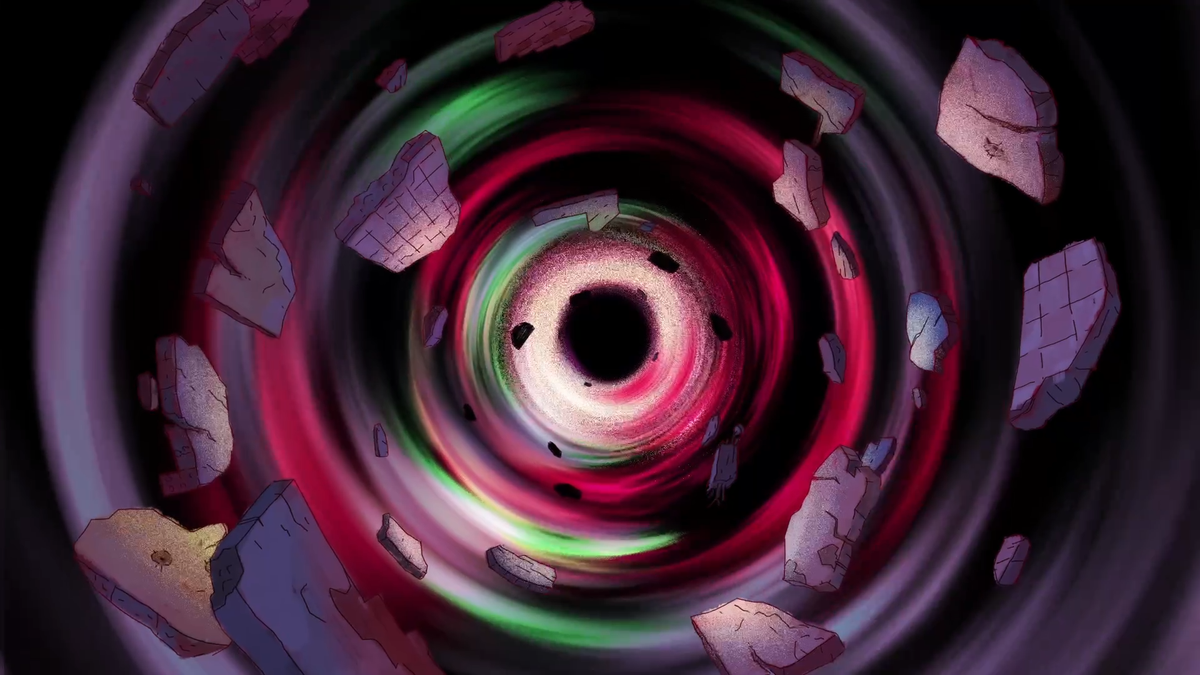

SEF: There's a few things that I want to talk about. I'm really thinking a lot about that Elias Khoury quote a lot because he passed away yesterday. That idea of the Nakba being an ongoing tragedy – an open wound – was a very visceral image for us. We have a few different devices that go back and forth between the realities: the reality where the Nakba happened and the reality where the Nakba never took place. One is the aerial shot of the circular square going into the animated vortex, which then brings us into the animated reality of Lyd. That aerial shot of that square is Palmach Square. It's significant because the Palmach is the Zionist militia who committed the massacre in Lyd in Dahmash Mosque. And that square is right in front of the mosque and is where the bodies were burned. So when Eisa Fanous, the older gentleman who talks about the Nakba, recalls being one of the 12-year-olds who was responsible for taking the bodies out of the Mosque and then burning them in the square — he's talking about that location. So that location became our open wound. And significantly, that location, that open wound, becomes the portal that takes us through to the alternate reality.

JW: I'm glad you explained that, and I'm trying to crawl back in my memory of viewing the film. I recall some shots of that aerial with a circle with some animation superimposed on it, something like a red circle. At the time, I don't think I was clear on what that is. Is that sort of the open wound thing?

SEF: Yes, exactly. And it's not explicit. Some people make the connection, some people don't. And that's totally okay. But, yes, it's those aerial shots. And then the kind of glitch effect comes in. And then it cuts to the animated vortex.

Jewish-American trauma, whiteness, and imperial collaboration

JW: I see how the open wound quote makes a lot of sense with the animated imagery. And I guess in a way – although this is not central to your film – the Holocaust works the same way in the psyches of a lot of Jewish Israelis and Jewish Americans.

SEF: Yes, I think that's very real. The way I think about it is this: My relatives came here as refugees before the Holocaust, but were fleeing antisemitism, fleeing the pogroms of Eastern Europe. They came with a lot of trauma, and that trauma has definitely been passed down. And I do see that wound, that trauma, similarly to how I see cycles of abuse in interpersonal relationships. I think we can understand our position, meaning the Jewish position, as having flipped from victim to aggressor, and see that as perpetuating a cycle of abuse. And I think it's really up to us to break that cycle.

JW: Can I ask you whether you personally grew up somehow with a feeling of inherited victimhood or not?

SEF: I think so. There are a few things I would share personally that I think are relevant. First of all, my family contains multitudes. In some ways, when I say I come from a traditional Reform background, I'm hinting at the fact that [on the one hand,] I was raised Jewish – I went to Hebrew school twice a week, I was Bat Mitzvah'd and all that stuff. But on the other hand, my mother was raised Catholic and my brother and sister are adopted from Colombia and no longer identify as Jewish. We are a very mixed family, we are not a homogenous Jewish family. Because of this, I'm really invested and interested in, and have a lot of hope for, the idea that spaces, like families and like nations, can contain different kinds of people, different positions, different religions, different races, different ethnicities. And I was taught that Israel was one of those places, that it was a socialist utopia. When I understood that it wasn't, it was almost like an assault on the things that I hold most dear. I feel like the existence of my family is in some ways challenged in this country, the U.S., where we still live with so much segregation. I was always led to see Israel as a place where things were different. And that's obviously just not true.

JW: So, in other words, you're saying that while the Israeli official in the film presents a vision of Israel as a multi-ethnic space as though it was the reality, you understand that vision to be a myth or just an official cover line?

SEF: Yes. Exactly. But, also, in terms of generational trauma: my grandparents on my father's side came from Belarus. They were refugees. And my grandfather was deeply, deeply depressed. And I know that this had to do with many of the things that he experienced there. And he was actually put in a mental hospital for Jewish people in particular who were suffering from trauma. That was in Westchester [New York]. (This was something that was not known to my dad. It was shortly before he and my aunt were born.) My grandfather received shock therapy at this place. Fast forward many years — my grandmother is picking me up from elementary school and realizes that the place is familiar. And it turns out that my elementary school was built on top of the hospital where my grandfather had received shock therapy for his trauma. So my father carries a lot of that depression, and it's certainly within me. I wouldn't necessarily call it inherited victimhood, but I do feel a deep kind of depression and the legacy of that within my family, tied to a sense of precarity from being Jewish and the antisemitism that they faced.

JW: Was there any time that you can remember feeling physically afraid or threatened because you were Jewish?

SEF: No. No, I've not felt that. And I think that's really different than my father and other people. But I think my embodied self is very, I would say, shiksa-presenting. [Laughter] And so I recognize that when I go into a space, people don't necessarily see me immediately as Jewish. And so it might be a very different feeling for somebody who presents as what people identify as Jewish. I think antisemitism is very real in this country. It's obviously having a resurgence. But I think the reality is that we — Jewish people who are white and Ashkenazi — assimilated to whiteness, and we hold a lot of power in this country. and I think that power shields us from a lot of actual physical danger that we could have experienced if we hadn't assimilated to whiteness.

"I do see that wound, that trauma, similarly to how I see cycles of abuse in interpersonal relationships. I think we can understand our position, meaning the Jewish position, as having flipped from victim to aggressor, and see that as perpetuating a cycle of abuse."

AL: The ability to serve American imperial interests writ large is the ultimate testament to the assimilation to whiteness.

SEF: Yes, which is what we're a hundred percent seeing now. And, really, the creation of the state of Israel has always served imperialist interests.

AL: Yes, although it was far more provisional … But yes, there's always been this sort of running current that you mentioned: that we can be in white spaces for the most part, even overwhelmingly white spaces, without really any sort of background worry of physical threat or even psychological threat. It's an interesting juxtaposition with the way we, Jewish people writ large, always present ourselves to the mainstream world — "We're under attack. Someone's going to kill us." — when we are ultimately in spaces where we don't have that to worry about, generally speaking.

On Coexistence

AL: Before I forget this — this is more a comment than a question — I really love how you let the city of Lyd speak for herself, how the film opens with Lyd speaking for herself. Okay, back to your story.

SEF: Lyd shares, in the voice of the city, that it's this history of colonialisms that formed the current situation. And then we unbuild that and build a different situation with a different history, where Pan-Arab armies drive out the French and British colonialists in what is known as "the Great Anti-Colonial War." The Sykes-Picot Agreement of 1916, which defined spheres of influence assigned to Britain and France (with assent from Russia and Italy), is never implemented. Instead, the states of Palestine, Syria, and Lebanon form a coalition-led country called the Greater Levant. And all this happens before 1948. So as Jewish immigration to Palestine, which began in the late 1800s, continues into the mid-1900s, Palestine is already free. Palestine is already liberated. So the question isn't, "What is going to happen with a Palestinian state?" It's already there.

And it was very important to Rami that this be a pan-Arab situation, to bring in Arab nationalism, but in a democratic way. Also, Arab nationalism is happening at the same time as Jewish nationalism. And as Jewish immigration continues with the escape from the antisemitism of Europe — the post-World War I pogroms and then the Holocaust — the question is: Would Palestine (now part of Greater Levant, in our alternate history) welcome these Jewish immigrants in? And our answer is: Yes. So Jewish immigrants are welcomed into the new state of Palestine and join existing Jewish communities.

In reality, we know from the Ottoman Census that in the late 1800s, before the First Aliyah [1882-1903], Palestine was 5% Jewish. Now there were larger Jewish communities in other parts of the region and 5% may sound like an insignificant number; but when you think about it, in comparison to the U.S., 5% is actually a larger percentage of Jews in the general population than we have [in the U.S.]. So it is a significant number.

Then you have to think, who would the heroes be? What would the city look like? What would be some of the significant landmarks that tell the story of how this cultural place came to be?

I was very influenced by a book by Salim Tamari, which is called "Mountain Against the Sea." It's a compilation of memoirs of Palestinians from before and during the period of the British Mandate. And a lot of the visioning and world-building in the film is drawn from that book. Obviously Rami is living this and has all of this embodied experience. So there was what he really wanted to put into it and what the people we filmed would have wanted to see. A few of the really important landmarks in the film's alternate-reality Lyd are drawn from these sources. Our elementary school in the alternate reality is named after Khalil Sakakini, a Palestinian Christian who is famous for rethinking pedagogy by using the Quran in Christian schools to teach Arabic. He was an Arab nationalist and he mandated that Arabic, not Turkish, be the official language of instruction in his schools. Another thing Tamari highlights in his book is that before the British mandate, Jerusalem was not divided into quarters, It was just everybody living together. And people really celebrated each other's holidays. So there were, for example, Muslims and Christians celebrating Purim; and there were these synchronistic symbols. St. George is one of those; St. George is also the patron saint of Lyd. It's thought that his remains are buried in the Church of Lyd. His mother was Lydawi [a native of the city of Lyd]. In the alternate reality, we make him into a symbol for the anti-colonial movement, like St. George killing the dragon is really the Palestinians killing the dragon of the British Empire during the Great Anti-Colonial War. So there are all these little things that come from actual history. (I think St. George is also the patron saint of England, so that's kind of a funny coincidence.)

Another thing that goes by really fast is, you see a bit of Hebrew in the alternate reality on a building. It says "Shami’s Pen" in Hebrew, "Shami’s Pen bookstore." And that is named after a Palestinian Jew who lived in Hebron before the State of Israel, whose name was Yitzhak Shami/Ishaq al-Shami. His mother was a Palestinian Jew from Hebron from before the first Aliyah. His father was a Jewish person from Syria. He grew up speaking Ladino and Arabic. He was a writer. When the state of Israel was founded, he stopped writing in Arabic and started writing exclusively in Hebrew. And so, in our mind, the Shami’s Pen bookstore is like a center for literature that would have continued if modern Hebrew hadn't been created and replaced all our great literary traditions in Yiddish and Ladino and Hebraic Arabic. Zionism created modern Hebrew, but in doing so, it ended all of that incredible linguistic plurality that used to be so intrinsic to Jewish culture. In our alternate reality, that tradition, those traditions continue.

JW: That certainly intersects with the Bundist vision of Yiddish. And we know about the Israeli campaign against Yiddish and the marginalization of Yiddish and other Jewish diasporic languages in Israel.

SEF: I could talk forever about all the different symbolism, but for the sake of time, I'll just say that we're about to put out an educational reader for the film that will have an alternate reality map of the city, with all of the landmarks and the symbolism of the landmarks explained. It should be available on the "Lyd" website in December.

Visions of what could be

AL: Part of what we're trying to do at Der Spekter, especially in the wake of the one-year anniversary of the Gaza breakout, is to try to posit a sort of alternative vision, because I think we're all more or less of the opinion, of the analysis, that the hope for a two-state solution is dead. Maybe we're taking it upon ourselves, but I think that the broad range of people who are disgusted by what's happening need to present an alternative vision from a Jewish perspective of what could be. And I think that the alternate reality that you and Rami built is an element of that.

JW: Yes, we call our publication Der Spekter, "spekter" being a Yiddish word which means both "spectrum," as in a spectrum of points of view, and "ghost," the vision that haunts our current reality, which points to a kind of alternate reality: what would've happened if the Bundist vision had —

SEF: My next movie!

JW: We'll raise money for it!

AL: Maybe we could get Molly Crabapple to do animation for it.

SEF: That would be incredible!

JW: Speaking about animation, I have three questions about the sci-fi animated sequences in your film. First, how did you and Rami go about creating those sequences? Second, how might you compare the ethos of that imagined world with the Bundist principle of national personal autonomy? It seems quite similar in many ways. And third, what is the nature of the political leadership of that imagined world? Who takes the place of, say, the colonial power that ruled until 1948?

AL: And just to add to that, I noted something like a pan-Arab thread running through the animated sequences. Was this referencing what was happening in, say, the 1940s? And, not to speak for him, but is this something that Rami brought into the story?

SEF: Well, I have a lot to say. I want to talk about both the world building that we did for our animated scenes, the idea of an alternate Bundist history and what that could look like, and then also this question of what the future could hold. As somebody who reads a lot of sci-fi fantasy, I really wanted to bring in what the backstory would've been to make this world different. Rami and I talked a lot about: what are the political flashpoints that we can address that, if we speculate that they could have gone a different way, they would have really changed history? And so we decided to start with, basically, the region driving out the Ottomans, and then also driving out the European colonialists. Because I think it's also important to remember that in the years following World War I, Palestine is coming off of some 400 years of Ottoman colonialism [1517-1917], Which is followed by European colonialism [1917-1948], and then Zionist colonialism [1948-].

AL: The alternate reality occupies such a small part of the movie, but the richness of the story that you tell and just how much thought you and Rami put into it is really inspiring and just wonderful. In this explainer of the alternate Lyd, are you guys going to dig deeper and tell more of that story?

SEF: I really wish we could. It was definitely my favorite part of making the film. But, you know, animation is extremely expensive. So, as you said, the alternate reality is a small portion of the film. I think it's probably cumulatively 20 minutes of a feature length documentary because it's just so economically prohibitive.

JW: I want to register a counter-opinion here. I think the fact that you give us those glimpses, which may be glimpses because of money reasons, but I think it's useful at least at this point in time, because if it had been the opposite proportion and it was, say, 70 minutes of animated alternate reality and 20 minutes of straight documentary, it would feel more like a campaign for a particular vision of how things should be. This way it's maybe more modest, but maybe more real for the viewer. I mean, for this viewer.

AL: Well, clearly that's why it left me wanting more!

SEF: Well, that's good. I like that. I'm glad. Thank you for saying that.

JW: In a way, it also says to the viewer: We're not trying to give you our prescription of what should be. We are just trying to give you a glimpse of what might have been and invite you to figure out, well, what would you like to have seen? What would you like to see for “the day after?” Which is, of course, the big question that everyone recognizes is missing from the current actors.

"I think it is also really important to recognize that in Palestinian liberation movements, there has always been the Jewish question. There has always been a reckoning with: yes, we want our liberation, but "from the river to the sea" did not mean an expulsion of Jewish people."

SEF: Yeah. You know, I was joking that my next movie is the speculative history of if the Bundists had won. But I actually think that's a really important thing for us Jewish people to talk about in the diaspora. In fact, I think that it's the most important thing for us to be talking about. Not necessarily what the future should be there, but what we can be building in the diaspora. To imagine what it could have been, and then to find and make that now.

Yesterday I went to the Jewish Currents Live event, and it was incredible.The final panel of the day that I went to was a panel of really incredible Palestinian journalists, lawyers, academics, and others, moderated by the editor-in-chief of Jewish Currents, Arielle Angel. And the title of the panel was “Palestinian Liberation after the destruction of Gaza.” Noura Erekat, a lawyer who was on the panel, put out a book titled "Justice for Some" in 2019. Full disclosure, I have not read the book, but on the panel she talked about how she concludes it with a very hopeful, speculative imaginary of a shared future and talks about Zionism also being oppressive to Jews — which I really believe. She also shared her complete disillusionment in this moment with that political imaginary, which I also totally get.

I really love the speculative oral history book titled, "Everything for Everyone, An Oral History of the New York Commune, 2052-2072", which is co-written by M. E. O'Brien and Eman Abdelhadi, a Palestinian woman. In one chapter, it imagines Gaza basically breaking through the border and liberating itself and then all of Palestine. It imagines a shared future that is Palestinian led, and that is inclusive of Jewish people who want to stay in liberated Palestine. Eman and I have been in conversation, and she did a talk-back at a screening of "Lyd." So there are obviously a myriad of opinions about the future and I think it's really important to recognize that there's a real disillusionment with any kind of future and political imaginary in this moment for Palestinians; and if I were them, I certainly wouldn't want to live with any of us, to be perfectly honest.

But I think it is also really important to recognize that in Palestinian liberation movements, there has always been the Jewish question. There has always been a reckoning with: yes, we want our liberation, but "from the river to the sea" did not mean an expulsion of Jewish people. Different people mean different things when they say it, but the expulsion of Jews was not the original intent of the phrase. It was intended to mean free movement of Palestinians from the river to the sea. In the 1970s, Fatah wrote a pamphlet that was specifically about the Jewish question and how to integrate Jews in a liberated Palestine. George Habash, who was the leader of the PFLP (Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine), which is a communist Palestinian liberation organization, talked about incorporating Jews in a liberated Palestine. This has not been something that has been absent from the political imaginary of Palestinians. And I hope that we can get back to that point, but it's not up to us. It's up for them to decide. And I think it's up for us to decide how we act. Do we support a genocidal state or do we support liberation for all people from the river to the sea? What world do we want to build in the diaspora? And hopefully the diaspora can include Palestine, when the time comes.

JW: Yes, very much. Have you seen the film, "Bunda'im"? It was made about 15 years ago by Eran Torbiner. It's a documentary about the remnant Bundists in Israel.

AL: Yes, there was, I think, an old leader talking on camera, smoking a cigarette. I think I've seen bits of it.

JW: Yes, it was … pretty depressing. Old people and how marginalized they have become in Israeli society, but how they still hold onto the ideals of their youth. I mean, it reminded me a bit of Eysaf (the artist who created the statue of St. George smiting the dragon).

SEF: Yes.

JW: So moving, when he makes that statuette, that sculpture. I felt a certain commonality there, with how the Bundist dream died a pretty quick death after 1948.

Seeing ourselves

AL: There is another scene in your film which comes to mind, a kind of an artifact of an Israel that no longer exists. I'm thinking of the clips of archival interviews with some of the Palmach soldiers who participated in driving Palestinian families out of their homes in Lyd in 1948. For two of the guys in particular, there is really a recognition of themselves, in what they had done. One of them says, "It was exile, it was galut" [the Hebrew word for the exile of the Jews from their homeland, now used pejoratively to describe diasporic Jewish communities].

SEF: Yes.

AL: It was like,"This happened to us."

SEF: Yes. Totally.

AL: And I'm not sure whether he was basically saying, "That massacre could've been a hell of a lot bigger." It's almost like he was saying, "I'll expel you instead of slaughter you…and that makes me feel better." But in that there seemed to be at least a recognition of humanity that does not exist today at all, at least from everything that we see in reports from Israel today. Some of that seems to be this transition from having experienced victimhood to full on becoming the victimizer, the weight of the accumulated trauma just pressing all the humanity out of you. What does it take, do you think, to get that society back to even that small recognition of our own history and ourselves in what Israel is doing to those people?

SEF: I think things really have changed a lot over the course of Israel's existence. My personal opinion is that Israel’s existence, since its inception, has come at the cost of Palestinian existence and that no religious supremacist states (like Israel) should exist. But Israeli society has changed and evolved from its inception, and it is not accurate to say otherwise.

For example, I understand that early on in Israel's existence, they assigned as mandatory reading in the school system the book Khirbet Khizeh. It's an Israeli novel about the Nakba from a soldier's perspective of destroying a village and expelling and killing people. And it's scathing. It's not even taking Ari Shavit's position of, "This is a necessary evil." It's, "This was bad." And that was mandatory reading. And it's not anymore.

When I talk to both Palestinian citizens of Israel and Jewish Israelis who have gone through Israel's school system now, they learn nothing about Palestinians or Palestine. And we see it in the scene in our film with Manar [a Lyd primary school teacher] in the classroom. Those kids really don't know anything, or know very little, about their culture.

So I think there has been a real manipulation, an erasure of the narrative that wasn't necessarily always there in Israel. So, I think you're absolutely right. I think that earlier on there was more recognition of the other. But I do think it was mostly with the caveat of: we need to exist by any means necessary, and our existence takes precedence over this other people's existence. And when you start with that as the premise, it's obviously only going to get worse. And the Jewish supremacy has gotten way worse. So, I don't think the goal is to “get back,” the goal is to have something else entirely.