A "Borough Park" for a radical Jewish present: an interview with Kleztronica musician Chaia

Yiddish techno “Kleztronica” pioneer Chaia samples Yiddish song to recreate her grandmother’s childhood in new single “Borough Park.”

Chaia (she/her) is a dance music artist who combines house and techno grooves with klezmer and Yiddish music. Chaia’s live performances feature vocals and instrumentals, layered over archival samples and modern club beats.

Abraham “Abe” Plaut (he/they) is a musician and activist currently based in Washington, D.C., where they are a member of the DMV Bund.

Abe and Chaia spoke about the growing Kleztronica scene, what a commitment to Yiddish music means in 2024, and the layers of meaning behind Chaia’s new single “Borough Park,” which was released on September 13, 2024.

Abe Plaut: So to begin, for a bit of background, can you talk about your Jewish journey and what brought you to this musical moment with Kleztronica?

Chaia: My dad is a Jewish Studies teacher. So I grew up with different people in the Jewish community (like educators, cantors, rabbis, and musicians) coming in and out of our house. I grew up going to Jewish day school. My dad teaches Kabbalah, and I grew up studying with him. I started singing in Yiddish and got involved with the klezmer scene as a teenager and went to The New England Conservatory. I’m still very involved in Jewish religious life.

Chaia performs "Borough Park" at the Sultan Room April 6, 2024

For me, the most important thing about Kleztronica is that it comes out of the tradition of Black American house and techno music. The history and tradition of Black American house and techno are rooted in Chicago and Detroit artists who made and [continue to] make liberatory music specifically for Black liberation. Similarly with Kleztronica, we’re using this liberatory music as a vehicle for Yiddish liberation and celebrating, supporting, and uplifting Yiddish culture.

AP: What does the Yiddish music world mean in 2024, especially in the wake of the bloodshed and crises in Israel-Palestine?

Chaia: Yiddish was just day-to-day life, day-to-day speech, language, and ‘being’ in Eastern Europe. In the late 19th century, you have the Modern Zionist movement coming up, and the Yiddishe Bund is saying, “No, if we go with Modern Zionism, we’re going to lose the things that make us Yiddish, the things that make us important.”

The broader Yiddish world was concerned about Zionism, but it was still a fringe thing to think of Yiddish as a radical movement. The Bund was radical, but Yiddish was mostly just day-to-day life. But there was a lot of radical culture within Yiddish, just as there is within every culture.

What started happening after 1948 is that Yiddish started to be taken out from the Jewish schools in the United States. People said, “We don’t want anything to do with Yiddish anymore,” and Yiddish became positioned as a language of the past, rejected in favor of Zionism and Hebrew. It became this binary between Yiddish and Zionism. Either you could study Hebrew in the schools and you could study about Israeli culture and language, or you could study Yiddish, Yiddish songs, Yiddish culture, Yiddish language. And there was a lot of pressure to choose Hebrew.

My dad grew up going to Jewish schools in Brooklyn and Queens in the 1960s without any Yiddish. But my dad still is surrounded by remnants — people who remember the old days of Yiddish and people who want Yiddish to [come] back. This was a fringe group of people who were bullied at his high school and called the “Yiddish crazies” in his high school. My mentor Hankus Netsky, who is a couple years older than my dad, grew up with Yiddish in his Jewish day schools and remembers being in the classroom when Yiddish was excised. Hankus is the transition point.

So Yiddish was partly accidentally anti-Zionist. It was more that Zionism positioned itself as anti-Yiddish. Yiddish was being stamped out in Israel, with people being beaten up for speaking Yiddish. Since then, people have really begun cleaving to the idea of Yiddish anti-Zionism that was present in the Bund, and it has become, among Yiddishists, primarily this radical thing. Yiddish is anti-Zionism because Zionism is anti-Yiddish.

"Yiddish has always been home in the diaspora; this is something that is as old as Yiddish is."

More recently (since the Lebanon War), more and more Jews have become disillusioned with Zionism because we’re seeing Zionism become more aligned with interests that are not Jewish interests. So there are more people seeking out Yiddish while becoming disillusioned with Zionism.

This is where we find ourselves in 2024. Obviously, a lot more people have gotten involved in anti-Zionist culture since October 7th. A lot more people have been looking for an alternative to Zionism or Israel as a vehicle for Jewish expression. The Yiddish music world and Yiddish cultural world have seen a big boom as more people become disillusioned with the idea of Israel being the safest place for the Jews. The illusion of safety in Israel is being shattered for lots of people, so people are looking for other ways to practice Jewish safety. Yiddish has often been a great vehicle for Jewish safety, Jewish community care, and Jewish collectivism in diaspora.

Kleztronica is one of those [Yiddish vehicles]. We came from this same idea of searching for safety in the diaspora.

AP: In what ways is Kleztronica also tied up with Queer Liberation? And intersectional solidarity more broadly?

Chaia: So much of Kleztronica is copy-and-paste from techno and house culture, and Black liberation in techno and house culture. All the queer parts are also copy and paste. A lot

of the techno and house DJs in Chicago and Detroit, and especially as the culture spread to New York City, were queer Black DJs. Queer, trans, every aspect of LGBTQ+ identity is represented in house and techno rave scenes. In a way, that’s because techno and house raves created relatively safe and liberatory spaces in cities where Black culture wasn’t given a fair place in the cultural landscape.

At the same time, in the 1980s, LGBTQ+ people were shut out, marginalized, and sent to underground spaces. In the underground, at the raves, queer culture could thrive and flourish. Kleztronica comes out of that tradition of house and techno raves.

On the other hand, queerness has been a big part of Yiddish culture for hundreds of years since the early beginnings of Yiddish theater and the days of traveling Klezmer musicians. Wandering, itinerant traveling artsy people, especially in a flamboyant medium like Yiddish theater, could express themselves beyond the boundaries of traditional Jewish society in Eastern Europe. We have drag Yiddish theater performers like Pepi Litman that we really look to as queer ancestors.

In the 1960s, Yiddish had become a somewhat fringe movement because it had been excised from so many mainstream Jewish spaces and replaced with Zionism. The hippie movement was coming up; Hankus was also there, and we’re seeing the hippies, folk music, and people like Henry “Hank” Sapoznik doing American folk music in different places in Appalachia. Someone asked Hank Sapoznik, “What about your own culture?” So Hank, along with many other hippies, started looking for his culture — something that felt real and historically grounded but also countercultural. A lot of these hippies, Jewish hippies like Hankus and Hank, found Yiddish.

On the other hand, queer artists like Adrienne Cooper [and] Alicia Svigals are thinking about how Yiddish is on the sidelines of Jewish culture, and LGBTQ+ identity is on the sidelines of Jewish culture, and how Yiddish has this queer history. So they’re working with Hank and Hankus on this project of the Klezmer Revival because they see that Yiddish has the potential to be a really big liberatory force for Queer Jews. Irena Klepfisz,a [lesbian] Bundist poet and lifelong activist] has an amazing interview with the Yiddish Book Center on this that I often sample in my music.

Read our interview with Irena Klepfisz here.

AP: You’ve said that “creating home in the diaspora is a really important thing” and that Kleztronica is a “version of what that looks like.” Can you talk more about what that means to build a home in diaspora? How does doikayt or hereness manifest in the Kleztronica scene that you’re helping to build?

Chaia: I don’t feel like I’m helping to build a scene; I feel like I’m practicing within a scene that already exists.

Yiddish has always been home in the diaspora; this is something that is as old as Yiddish is. For me, growing up around Yiddish musicians, around Klezmer music, it feels like this is a tradition that I’m just joining. It is a tradition that we can enrich by creating new things within it, like people have always done. But it is a tradition that is deep, that is rooted, that exists, and that we’re joining the ranks of [feeling at] home in the diaspora.

The Bund has this idea that Jewish safety comes with solidarity. Doikayt is about supporting the people around us. Hereness as in joining the labor movements. Hereness as in collaborating with non-Jews to ensure Jewish safety in the diaspora, and to ensure collective safety through worker’s rights, through different minority group rights, through class solidarity. To me, I think doikayt is really about working with what you have and working with the communities that already exist around you. The Yiddish community is so beautiful, and the communities in New York are so wonderful, and the communities in techno and house and all these existing communities are so amazing. So for me, the most powerful thing I can do to ensure my community’s safety and my community’s care is to build collectively with the people around me who are already doing such powerful work.

AP: What does it mean to address the “trauma of Zionism” in your musical compositions and live shows?

Chaia: I always come back to this Hankus interview with the Yiddish Book Center. There’s some genius at the Yiddish Book Center who cuts these interviews and oral histories into short clips, each on a different topic, so you can search for a certain topic at the Yiddish Book Center and find lots of great interview clips.

I studied with Hankus at the New England Conservatory, and in this interview he talked a lot about the grief of the decimation of Yiddish. And the grief that after the Holocaust, so many Jews wanted to turn [their] backs on Yiddish in favor of Zionism. For Yiddishists, that’s the big loss for our culture. The abandonment and loss of Yiddish language, music, and culture. Burying our songs, which were once really well known, into archives.

There’s lots of traumas of Zionism; I’m not even going to go into detail about the death, destruction, imperialism, and witnessing bloodshed, especially now in the social media age. Seeing bloodshed — that’s not specific to my experience, so it’s not something I want to talk too much about because it’s a worldwide experience and anyone can see that for themselves.

Something that’s really specific to me is how my people’s language and culture and world was basically abandoned. People turned their backs in favor of Zionism-as-safety. With Kleztronica, it’s really important for me that we’re digging up this culture. We’re digging up these songs out of archives. My personal work in Kleztronica is all about two amazing, amazing archives: Itzik Gottesman’s Yiddish Song of the Week archive and the Ruth Rubin archive at YIVO. These archives are curated and made by people I love, and putting these archival tracks on in the nightclubs and making hundreds of people listen to them and accept them and believe in them and feel what they’re saying is my love letter to all these wonderful people who help organize the archives. The trauma most close to my own personal experience is the trauma of lost Yiddish culture and music and song; people being ashamed of Yiddish. In Kleztronica, it becomes popular music, a liberatory vehicle, and a way to bring its radical history to light.

I will say that certain strategies of safety lead to lots of death, and other strategies lead to life and culture flourishing. We have a lot of Jewish history; we have a lot of death in Jewish history. We carry that with us. Even before Zionism, we have been persecuted for so many years; we have fought wars. At the end of the Purim story [in Chapter 9 of Megillat Esther], we kill 75,000 people. There is a lot of blood on our hands and blood we have lost. As much as we can find ways to cope and mourn the violence in our history, we can find hope and new life and new safety.

"I think that really represents the vision of the Jewish world I want to see. A Jewish world that doesn’t use force to solve problems, that doesn’t discriminate against denomination or background, or any of these things that divide us or create hierarchies."

AP: With your upcoming new music, your new album, and the lead single “Borough Park,” can you talk about what’s in that song? What are the samples you’re pulling from?

Chaia: The first sample is my grandmother speaking, an excerpt of a story she told me about her life growing up in Borough Park, the neighborhood in Brooklyn, New York City. I have this recording I took of her telling me this story and many more that will find their way into other songs on the album. Each song on the album is wrapped up in one of her stories. Her stories are amazing because they are snapshots of Jewish life in the 1930s. Pre-Holocaust, pre-1948, they’re snapshots of the different kinds of liberations that were possible with a decade less of generational trauma. This is a kind of liberation that I still think we can make possible today.

The second sample I’m using is from The Pennywhistlers. Ethel Raim, an amazing Yiddish singer who co-founded the Center for Traditional Music and Dance, founded a choir called The Pennywhistlers. They did lots of Eastern European folk music with a focus on Yiddish music. The sample is from a song called “Oyfn Oivn,” which is about two people sitting on an oven. A girl is sitting on an oven with a thread; she’s sewing a silk scarf. A boy comes running by and yanks on the thread, and she says she’ll make him fall in love, but not by force, not with her hands; she doesn’t care about his background, but just with care and with love.

I think that really represents the vision of the Jewish world I want to see. A Jewish world that doesn’t use force to solve problems, that doesn’t discriminate against denomination or background, or any of these things that divide us or create hierarchies. This is a vision that my grandmother really experienced in Borough Park in the 1930s that she told me stories about. A vision [of a world] with fewer boundaries, less stratification. This song [“Oyfn Oyvn”] feels perfectly representative of that vision. There’s also this cheeky element to it because it’s a metaphor for sex. At the end of “Oifn Oivn,” it says “two people are sitting on an oven, and neither person is knitting or sewing,” and it’s this moment when the listener puts two and two together and realizes they’re having sex.

Some Hasidic groups have taken this song and changed the lyrics to become religious lyrics, and I think it’s kind of funny that we now get to sing it again in this more cheeky meaning. Several ex-Hasidic people have come up to me after my performances and said to me, “I heard that song totally different growing up,” so I think it’s great to re-introduce people back to this type of Jewish life where things were more freely moving between religious and cheeky profane spaces. There’s sex and mixed dancing, but it’s in Borough Park, and people are still living a traditional, orthodox Judaism. It’s a vision of very pluralistic Jewish life. That’s really what the song is about: pluralistic Jewish life that comes from care and love. It’s Ethel and her choir singing this song; those are the voices you hear singing in that sample.

I studied Yiddish singing with Ethel; she’s a very important person in my life. So my song “Borough Park” is also an homage to her.

In addition to the archives, I have different Klezmer musicians that are playing on this track that I recorded myself with engineer Andres Abenante. There’s Rachel Leader, Raffi Boden, and AANI. There’s also two amazing jazz musicians, Vi Reiss and Hana Igarashi. In the very background of the track, you can also hear Hadar Ahuvia, Noam Lerman, and Basya Schechter on vocals.

Below is an artist statement written by Chaia and originally published by Der Speker on Sept. 5, 2024.

How do the echoes of the past guide us toward liberation in the present? This is a question that centers my work as a Yiddish music practitioner and techno artist. Sampling, a practice with its roots in Black American music, has long been a way to summon the voices of ancestors, weaving them into new narratives. House and techno, born as vehicles of Black liberation, have historically sampled Black music, speeches, and sonic landscapes to craft radical spaces of cultural expression. In my own practice, I extend this lineage by sampling the music of my Yiddish ancestors, using techno as a medium for cultural liberation, remembrance, and radical solidarity, pulling Yiddish history into a shared, ecstatic space. Yiddish, with its long history of queerness, activism, and anti-Zionist movements, beautifully obliges.

In “Borough Park,” I bring my grandmother's voice into this ecstatic space. She speaks of her childhood in Borough Park, Brooklyn—a world marked by a fluid orthodoxy, one that, though tight knit and unyielding, bent and shifted with the evolving communities around her, one that rejected insularity in favor of joyous pluralism. In my grandmother’s recollections of mixed dancing at her local community center, there’s a wildness that resonates with the rave culture where this track now lives. To me, the pulsing beats and flashing lights of the rave are not so different from the energy she describes.

Layered into this track is a 1965 recording by Yiddish song pioneer Ethel Raim and her group “The Pennywhistlers.” Their song “OYFN OYVN” tells a playful tale of a girl and a boy on an oven—an encounter charged with desire and sexuality. The girl says: “I won’t ask you where you’re from, I won’t tie you with rope, but I will embrace you and I will love you and you will remain.” This story, one of love without force and regardless of background, stands in beautiful conjunction with my grandmother’s story of pluralistic identity in Borough Park. Ironically, modern popular renditions have censored all mentions of sex and free love.

Through these samples, my work explores how Yiddish folklore and personal memory can be repurposed to serve as tools for contemporary cultural reclamation. Integrating these ancestral voices into techno is not just a musical project. Rather, it’s a political project of diasporism, activating spaces where history, culture, and liberation intersect. By bringing these voices into modern, communal spaces, I aim to transform collective memories into shared experience, emphasizing the joy of engaging in fluid community and solidarity in diaspora.

Listen to “Borough Park” by Chaia available on all streaming platforms September 13.

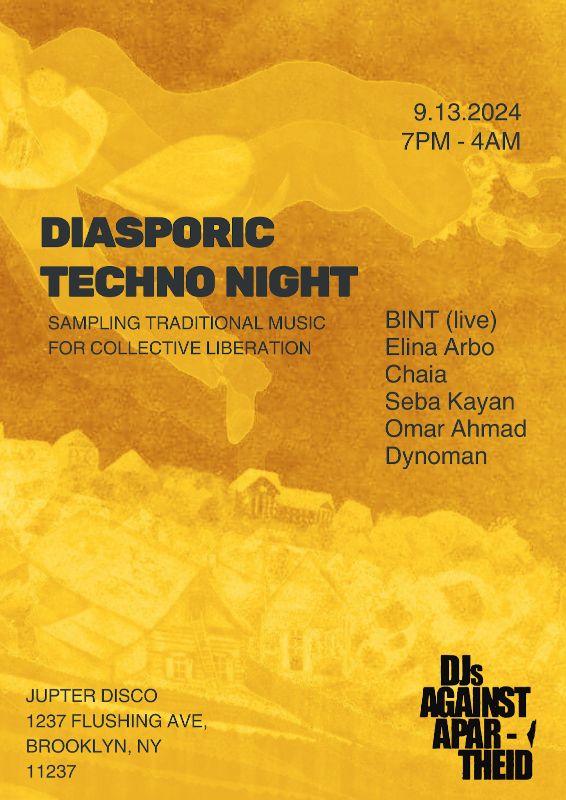

There will also be a release party on September 13 in Brooklyn at Jupiter Disco from 7PM-4AM, featuring 6 electronic practitioners (Omar Ahmad, Seba Kayan, Dynoman, Elina Arbo, BINT, Chaia) from different diasporas. The party will serve as a fundraiser for DJs Against Apartheid.

For more info and updates, follow Chaia on Instagram @chaialeh, find her website chaia.online, or email her at chaialehmusic@gmail.com to be added to her email list.