To Hold the Line: Sumud, Doikayt, and the Syntax of Shared Struggle

When Hashem, the Name, the Life of the Worlds, cries out to us: "Ayeka (where are you)?" We respond with: "Hineni (I am here)!" I am here to hold the line.

"It's a sign of the ages, markings on my mind.

Man at the crossroads, at odds with an angry sky.

There can be no salvation, there can be no rest,

Until all old customs are put to the test.

The gods are all angry, you hear from the breeze,

as night slams like a hammer, yeah, and you drop to your knees.

The questions can't be answered… You're always haunted by the past….

The world's full of children who grew up too fast."

~ Gil Scott-Heron, “A Sign of the Ages,” Pieces of a Man (1971)

...

When הַשֵּׁם, (Hashem, the Name), the Life of the Worlds, cries out to us:

"Ayeka (where are you)?"

We respond with:

"Hineni (I am here)!"

I am here to hold the line.

The sun floods the sky above Masafer Yatta – it is only midday. I am sitting in the shade, on the patio of a remote Palestinian home in the community of Um Dorit; it is sweltering outside, and I am trying not to bake. My friend would later turn to me as we were trudging along the rough terrain, grazing with the shepherds. “I’ve hit a wall with this heat,” they’d tell me. “I was built for the shtetl, not this.” We laugh. I’ve spent the better part of the past week here completing a solidarity shift hosted by the Center for Jewish Nonviolence (CJNV). CJNV was born from a conversation in 2014 between Ilana Sumka, former Jerusalem director of Encounter, and Daoud Nassar, whose family owns the world-renowned Tent of Nations compound, after the Israeli government tried to uproot the Nassar family farm. Daoud invited Ilana to organize a delegation of Jews to replant trees as an act of solidarity. Since 2015, CJNV has brought Jewish internationals to the West Bank to leverage their privilege in supporting Palestinian-led initiatives against Israeli state-settler terrorism. The organization is fiscally sponsored by Nonviolence International, founded by Mubarak Awad – a psychologist and primary organizer of the demonstrations against Israel during the First Intifada (1987-1993), who was deported by the late Prime Minister (and butcher of Deir Yassin) Yitzhak Shamir in 1988.

We weren’t even supposed to be here. We were originally staying in Khirbet Susiya. Several activists were arrested in at-Tuwani a couple days back for protesting against the demolition of a Palestinian home. The solidarity ecosystem here is remarkable, but the arrests have spread us awfully thin. Some CJNV folks will have to switch out with a pair of activists from the International Solidarity Movement (ISM) over in Um Dorit. They need at least two for the overnight swap.

Four of us are in Khirbet Susiya. Six others are in Umm al-Kheir. Khirbet Susiya is spread wide across the South Hebron Hills, so wide that two people cannot possibly provide enough coverage here themselves. The village is suffocated between a nearby antagonistic Jewish settlement (also called Susya) and the site of Ancient Susya, home of the original Palestinian village; residents were exiled from there in the 1980s when the Israeli Defense Ministry’s Civil Administration claimed the land as an archeological site containing the remnants of an ancient synagogue. Biblical archaeology, at times with fervent Christian evangelical support, is often used to justify Zionist colonization. Before that, the records of Palestinians living in this area dated back generations. A number of families also arrived here as refugees from the Nakba of 1948, fleeing from places like Arad in historic Palestine on the edge of the 1949 Green Line. Despite having already endured multiple expulsions, residents in Khirbet Susiya and other Palestinian communities face continued displacement efforts from agents of the Israeli state in league with settler nonprofit organizations such as Regavim; Regavim was founded by none other than the current ultranationalist finance minister of Israel, Bezalel Smotrich.

The latter group in Umm al-Kheir has more people, so we ask in our Signal chat if a couple of them could go. We quickly find out that they can’t; two of the activists have gotten sick, and the rest are desperately needed. A week before our arrival in the region, the Bedouin residents of Umm al-Kheir faced some of the greatest violence in their history, in the form of 11 home demolitions. The Jewish settlement of Carmel sits right in their backyard. Fuck, this is impossible. Somewhere will inevitably be left exposed. Ultimately, two of us in Susiya offer to go to Um Dorit.

When we first arrived in Khirbet Susiya a few days ago, Hamdan Ballal, one of CJNV’s community partners, took us on a tour. Hamdan is one of the four co-directors of the new award-winning documentary “No Other Land,” set in Masafer Yatta; two of the co-directors, Yuval Abraham (an Israeli Jew) and Basel Adra (a Palestinian from Tuwani), were accused of antisemitism by German politicians for remarks made upon receiving the 2024 Berlinale Documentary Award back in February. Hamdan is one of our main contacts in Susiya, alongside his neighbor, Nasser Nawaja. Both men have spent years documenting and resisting state-settler violence. Since October, Hamdan has split time between his community and immediate family, who have had to move to nearby Yatta (in Area A) for their safety. Nasser’s family remains in Susiya. His father, Muhammad Ahmed, whom I had the pleasure of meeting, is himself a community leader and subject of the short documentary “Susya.” He is a survivor of the 1948 Nakba.

Strolling about while gathering my thoughts, I notice Jerusalem is more segregated than I remember it, between Israeli Jews and Palestinian Muslims or Christians. It is the beating, bleeding heart of a Jewish Sparta; plenty of people openly carry rifles throughout the streets of the Holy City.

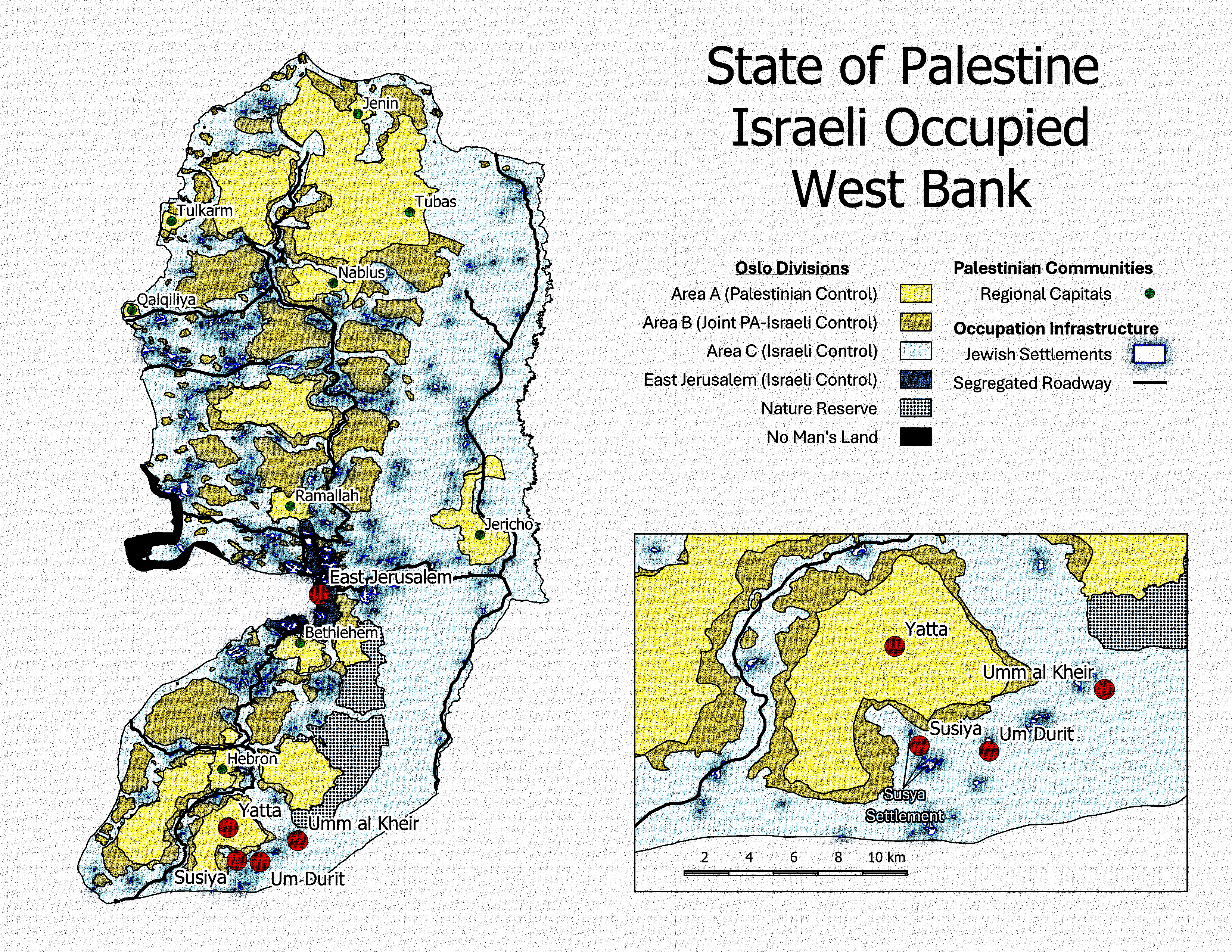

I do my best to stay present on Hamdan’s tour; I keep mentally reviewing the protocols given to us by CJNV organizers during our four-hour legal training in East Jerusalem: the differences between being arrested by the Israeli police versus detainment by the army; a “closed military zone” versus a “firing zone”; the different modes of legality between civilian and military laws. Jurisdictional distinctions between Areas A, B, and C. We have the right to remain silent. Interrogations happen. We should lock our phones with a good passcode. Stay quiet. No small talk with soldiers or cops. Nothing “off the record.” Everything we say can and will be used against us. Always speak to a lawyer first. Someone from B’Tselem (the Israeli Information Center for Human Rights in the Occupied Territories) may serve as legal counsel. Deportation orders can be distributed on wide grounds. In the field, “hurry up and wait” is the name of the game. Hurry up and wait. Hurry up and wait. Anything could happen at any time. We are there for de-escalation, but we also look to our Palestinian partners for guidance. In any and all scenarios, the people here will bear the consequences of whatever we do or don’t do. Too often, a family’s biggest fears come true. No pressure.

In a bizarre sense, it’s a relief to be here. Leaving the U.S. was hard emotionally. To say my parents weren’t thrilled about my trip would be an understatement. I told them I was going only a couple of days beforehand. They really are good parents, but I just knew they would try to talk me out of it. My friends are generally more supportive. Still, one of them says to me half-jokingly, “Sam – if anything happens to you, I am joining Hamas.” The night before I leave, my sister drops by to bid me farewell. She tells me she is proud of me and gives me a big parting hug. “Love you, dude. Fuck ‘em!”

My first night in the country scared me. I have visited twice already; the last time was with a youth group in 2014. Before that, I came with my family the summer before my Bar Mitzvah in 2010. Walking off the plane last July, posters on the jet bridge advertise the International Fellowship of Christians and Jews in all of its cynical, armageddon-goading glory. “Bring Them Home” portraits of Israeli hostages line the terminal exit of Ben Gurion Airport. The atmosphere is heavy with national grief. I take a train and stay in a Jerusalemite hostel. Strolling about while gathering my thoughts, I notice Jerusalem is more segregated than I remember it, between Israeli Jews and Palestinian Muslims or Christians. It is the beating, bleeding heart of a Jewish Sparta; plenty of people openly carry rifles throughout the streets of the Holy City.

“Islam came to us,” he said. “Our ancestors are the Canaanites. They worshiped the sun and the moon. Islam came later and included what came before: Ibrahim, Ishaq, Yaqub, Ismail, Musa, Isa…Muhammad was the last.”

Once I arrive in Masafer Yatta after the brief training, I feel more grounded. Shepherds graze with their herds early each morning, over hills that were once used as ancient wine cellars for the Romans and Byzantines. Hamdan gives us a portable camera so we can document invaders from Jewish Susya. Shabbat, traditionally a day of rest in Judaism, mutates into a day of holy war for the settlers. Bastards. We are told which roads separate Area B from Area C, where to go, where not to go. Class divisions enable Palestinians in Area B to build on their land, while the residents of Khirbet Susiya in Area C cannot. They are “Arab mustautin,” or Arab settlers, as one shepherd would tell me with a smirk. Hamdan introduces us to other families. As he guides us, I notice many of the homes have plaques on them denoting humanitarian funding from European NGOs. The international outcry from these organizations was one of the only things that kept Khirbet Susiya from being bulldozed by the Israelis in 2015. Hamdan’s mother hosts us for lunch. I am profoundly moved by the generosity of everybody here. The food is so fresh. The delicious za’atar is green gold from the ground. I don’t think I ever drank so much tea.

Hamdan tells us how Jews come here and accuse them of being Muslims alien to the land. “Islam came to us,” he said. “Our ancestors are the Canaanites. They worshiped the sun and the moon. Islam came later and included what came before: Ibrahim, Ishaq, Yaqub, Ismail, Musa, Isa…Muhammad was the last.” Judaism had adopted the Canaanite mythos, Christianity built on those, and then Islam absorbed them all. For centuries, cultural fluidity existed between these three Palestinian faith groups, facilitated by the perception of Jews and Christians as ahl al-kitab — “People of the Book” — supported by traditions of religious pluralism during the Islamic Golden Age. European-style nationalisms drastically shifted the political landscape when they were injected into Western Asia with the collapse of the Ottoman Empire at the end of World War One (1914-1918).

Hamdan’s oral history is reinforced by the work of both Israeli and Palestinian scholars. Nur Masalha, a Palestinian historian, counters Zionist historiography in “Palestine: A Four Thousand Year History” by suggesting that today’s Palestinians are the multi-layered descendants of local Jews and Christians, most of whom converted to Islam sometime after the conquests of Muslim caliphates beginning in the 7th century CE. Israeli historian Shlomo Sand, in his controversial book “The Invention of the Jewish People,” highlights theories from key Zionist leaders like David Ben-Gurion, Israel’s first prime minister, and Ber Borochov, a founder of the Labor Zionist group Poalei Zion. These men also entertained the idea that many of the Palestinian fellahin (“rural peasants”) are closely descended from the ancient Judeans who dwelled in the land since the Bar Kochba Revolt in 165 CE; many Jews, or so they thought, converted to Islam to enjoy taxation privileges under the ruling caliphs.

I ask Hamdan about normalization and what it means for the CJNV solidarity shifts. CJNV’s “co-resistance” frame supersedes the “coexistence” approach of the Oslo period; it is one of many strategies used with its own set of advantages and paradoxes. Different opinions on what constitutes normalization also circulate movement spaces, with many groups gauging the value of certain actions and political alliances based on how they adhere to Al-Thawabit al-Wataniyya (“fundamental principles”) codified in the national charter of the Palestinian Liberation Organization. The Thawabit has consistently maintained the Palestinians’ inalienable rights to self-determination (with a capital in Al-Quds/Jerusalem), to armed resistance, and for a return to lands where families had been expelled by the Zionist project. Hamdan says that he is glad there are Jewish Israelis who experience a change of heart concerning the Occupation. Many of them proceed to leave the country for Europe or the United States, not wanting to participate any further. He tries not to judge them, but perhaps this choice is too easy. Hamdan thinks they are running from their responsibility to stay and fight – to resist alongside Palestinians.

I will dwell on his words for the remainder of my stay. Things have remained relatively calm in Khirbet Susiya – but just as we watch the settlers, we too know that they watch us. They drive slowly along the roads to Jewish Susya, windows down, keeping track of how many internationals are around. Sometimes settlers like to send small drones out to hover and spy. If a few activists leave, will they decide to attack? Our presence seems to have deterred the usual harassment, so our host families worry about what might happen if a couple go to Um Dorit. A settler-soldier, stalking from afar with a government-issued rifle, could easily take the opportunity to assault one of the Palestinian shepherds. He might send children on donkeys armed with sticks to beat them instead, or destroy a local well. This strategy is especially sinister because it is illegal to publish videos of minors. Jewish settler children are regularly weaponized for colonial land-grabbing.

Left: An early morning out grazing with the shepherds in Susiya. Right: The late afternoon sun, peeking through barbed wire. Photos courtesy Sam Sherman.

When I get to Um Dorit, we quickly touch base with our ISM counterparts and I start entertaining the two young boys living there as their family wraps up a day of work. The family seeks to renovate and reconstruct their home – a precarious task, considering the inability for Palestinians residing here to obtain building permits on their own ancestral lands. Agents from the state could arrive and halt their work at any time, as Israel retains full civil and security control over Area C. Area C contains sixty percent of the West Bank; when you factor in joint PA-Israeli security coordination in Area B, Israel presides over roughly eighty percent of the territory. The settlers in nearby Avigail, of course, have hardly any problem obtaining permits for themselves, even though the construction of Israeli settlements is considered illegal under international humanitarian law. The Palestinian family here must build swiftly if any progress is to be made on their home. They are under constant threat from Jewish fundamentalists and potential pogroms. One of their pickup trucks was torched by Jewish “neighbors” not too long ago. Their tractor was also stolen, but they managed somehow to get it back.

The conditions of the Palestinian family's home in Um Dorit exist in stark contrast to the Jewish homes of Avigail. The settlement has lush trees, fully paved roads and, most importantly, clear access to running water. Many of the settler-soldiers patrolling the hills have been effectively deputized by the state. There is no distinction left between the settlers and the army. Some have reportedly worn patches pairing a skull with the Star of David, borrowed from the “Punisher” symbol used by far-right groups in the U.S (similar to the SS Totenkopf). It is all clear as day and worse than it’s ever been: the Zionist colonial regime is thrusting toward full annexation of the West Bank.

The two of us from CJNV watch for activity coming from Avigail and its corresponding outpost, perched on an elevated hill a short jaunt across the valley. A lookout booth from the outpost sits empty but forebodingly close to the property of my Palestinian hosts. Two poles stand on either side of the booth, with matching blue-white Israeli flags waving furiously in the dry summer wind. Hatikvah (“The Hope”), the Israeli national anthem, was one of my favorite songs to sing in student minyan at shul growing up. I have chosen to hospice that joy given what I know now, but I can’t stop the melody from ringing in my brain.

Masafer Yatta has taught us the meaning of sumud – the Palestinian cultural virtue commonly translated as “steadfastness.” Dr. Lara Sheehi, assistant professor of clinical psychology at George Washington University, defines sumud as a “social and political project. It’s not just a thing I do. It is a larger structure of maintaining commitment to the liberation of Palestine, to maintaining presence, to maintaining psychic clarity...” As early as the 1936 Great Revolt, Palestinians across all social classes dedicated themselves to sumud in the face of Zionist colonialism and British imperialism. The Zionist movement had steadily grown in power under the sponsorship of the British, who sought to administratively bypass the existing Palestinian clerical elites previously endeared to the Ottomans. The indigenous working class, overwhelmed by mass immigration, were excluded from the trade unionism of the Labor Zionist newcomers and their exclusive campaigns centering Hebrew workers. Peasants found their agricultural livelihoods upended by Zionist dealings with feudal landlords.

The Jewish community existing in Palestine prior to the First Aliyah (1881-1903), primarily of Sephardic or Shami (Levantine) backgrounds, along with a small group of Ashkenazi pilgrims, were all gradually adopted into the Zionist project. Like eventual waves of Jewish immigrants to the new State of Israel from the Maghreb and Mashreq, many Jewish Palestinians struggled to navigate mutually exclusive notions of Jewishness and Arabness. Overall, the Jews of Arab lands and Iran were collectively resocialized as mizrahim (“orientals”). Immigrants were traumatized in Israeli ma’abarot (“absorption camps”) and systematically Zionized by the Ashkenazi ruling class to be used as a political cudgel against Palestinian refugees.

The socio-economic and physical displacement experienced at all sectors of Palestinian society by the time of the Great Revolt (1936-1939) led to a massive wave of general strikes alongside parallel threads of militancy inspired by Syrian imam Izz ad-Din al-Qassam. Though some, like Palestinian revolutionary Ghassan Kanafani, theorized that the losses sustained in ‘36 clipped the momentum of organized Palestinian resistance to adequately respond to the catastrophic expulsion of 1948, al-Qassam’s memory nonetheless paved the way for a legacy of resistance lasting the better part of a century. Many organizations of varying ideological orientations have sought to take up the mantle: the social democrats of Fatah, the Marxists from the Popular Front and Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine, Sunni nationalists like Palestinian Islamic Jihad and Hamas, smaller anarchist formations like Fauda, broader coalitions such as the Popular Resistance Committees and Tulkarm Battalion, and non-partisan units like the Jenin Brigades and Lion’s Den.

The last thirty years since the collapse of the Oslo Accords saw whatever historic unity achieved under the PLO progressively disintegrate. Israel’s manufacturing of a perpetual genocide against the Palestinans, with impunity derived from unconditional U.S. support, has accelerated the “bantustanning” of the West Bank – cordoning off enclaves where Palestinians are deprived of full political rights under the guise of ensuring future “statehood.” The brutal blockade of Gaza, annexation of East Jerusalem, disputes of status faced by Palestinian citizens of Israel, the purgatory-like state endured by refugees in camps across Bilad al-Sham (the Arabic term for the Levant, or “Greater Syria”), and the development of significant diasporic communities in countries like Chile and the United States, have all contributed to fragmentation among the wider Palestinian body politic. Normalization efforts with Israel have been undertaken by neighboring countries like Egypt, Jordan, and Saudi Arabia, leaving Palestine isolated as those states seek to revitalize their economies with access to Western capital and solidify their domestic authority with Israeli war tech.

Meanwhile, Israel has employed endless arrays of divide-and-conquer tactics between Hamas in Gaza and the rival Palestinian Authority of the West Bank. With factional divisions exacerbated by the Occupation, many Palestinians have come to see the PA and its president Mahmoud Abbas as collaborators with Israel’s advanced security apparatus, while Hamas’ implosive struggle to navigate democratic governance with resistance measures has hurt its wider reputation both within the Gaza Strip and internationally. There are those who have been frustrated with the leadership of Hamas’ political bureau, but many identify bravery with its military wing, the al-Qassam Brigades, and other militants taking up arms against Occupation forces. The complexities and sophistication of the Palestinian Resistance should not be overlooked by those in the West.

Throughout history, many Palestinians have also chosen tactics of nonviolence, which were prevalently used during the First and Second Intifada, the Great March of Return in 2018, and the 2021 Unity Intifada. Over the years, Masafer Yatta has been a bastion of nonviolent resistance. Its isolation from the northern militancy of West Bank cities like Jenin, Tulkarm, or Nablus leaves Palestinians vulnerable to attack by Jewish settler-soldiers working to ethnically cleanse them from Areas B and C into the enclaves of Area A. The Palestinian communities here partner with solidarity groups like Youth of Sumud, Youth Against Settlements, Faz3a-Defend Palestine, CJNV, ISM, All That’s Left, Ta’ayush, Rabbis for Human Rights, and other allies operating in loose networks. A couple of experienced Jewish Israeli activists with Ta’ayush visited Susiya during our stay. Demonized as “anarchists” by government officials, they are weathered and weary from holding the line. Support from their countrymen is slim. The future is a terrifying void.

The boys in Um Dorit and I play rounds of “slap-hands” and watch SpongeBob SquarePants on my iPhone. Imitating the sound of SpongeBob’s signature high-pitched laughter, I repeatedly flick the ridge of my hand against my Adam's apple. It cracks them up. It’s good that we came here. Last night, a large party of settlers – over 50 to 60 cars – gathered at the local outpost. I was told that Smotrich might even make an appearance. I imagined the worst would happen. Thankfully, nothing occurred. We are to stay here through the rest of the day until someone else can cover for us.

I get tired of playing with the kids and put on my headphones to listen to some music. “Zombie” by the Cranberries comes up. It was written about the Troubles in Northern Ireland. Lingering guitar riffs drone on as Dolores O’Riordan’s Irish brogue wails over the dunes of the Naqab (Negev) off in the distance:

“It's the same old theme, since 1916

In your head, in your head, they're still fightin'

With their tanks and their bombs

and their bombs and their guns

In your head, in your head, they are dyin'

In your heeeeaad, In your heeeaaad,

Zombie, Zombie, Zombie-ie-ie…”

The boys notice my headphones. They want to try them on.

“Hilweh!” (“beautiful” in Arabic) exclaims Bashar, the older of the two, when he sees me wearing them.

I’m glad he trusts me. Last night, he noticed the Hebrew letters tattooed on my right bicep.

“Hebroni?” he asked.

His eyes widened. He thinks I could be a settler from Hebron. My tattoo spells out the word שְׁמַע (shema, “listen”) – the root word from the first part of my Hebrew name, שמואל (Shmuel).

“Hebroni?” Bashar asks again.

The only Jews this kid knows are the ones who routinely harass or attack his family. A few months ago, a video went viral online depicting a trio of thuggish settlers sitting casually in the family’s home. The settlers left soon after they started being recorded, but threatened to return: “We will come back and you will make us coffee.”

I reassure Bashar that I am not a settler. A mischievous, boyish grin returns to his face. Over the course of my stay, we speak to one another in what little English or Arabic we each respectively know. Google Translate helps fill in the gaps. It is far from perfect; the translations don't always correlate well with the colloquialisms of the fellahin or bedawi (Bedouin) dialects spoken in Masafer Yatta. It will have to do.

The younger boy, Khaled, wants a turn with my headphones. I have to hold them in place over his large ears so they stay up on his small round head. I know this family tends to lean more socially conservative. I don’t want to play anything that offends. So, I cycle to a version of the adhan (Muslim call to prayer) on my music app:

اَللَهُ اَكْبَرُ- اَللَهُ اَكْبَرُ / Allahu Akbar, Allahu Akbar

Sparks of recognition light up the eyes of the two boys. I know a little and we sing softly together

اَللَهُ اَكْبَرُ- اَللَهُ اَكْبَرُ / Allahu Akbar, Allahu Akbar

اَشْهَدُ اَنْ لَا اِلَاهَ اِلَّا اللهُ / Ashhadu an la ilaha illa Allah

اَشْهَدُ اَنْ لَا اِلَاهَ اِلَّا اللهُ / Ashhadu an la ilaha illa Allah

اَشْهَدُ اَنَّ مُحَمّدًا رَسُولُ اللهِ / Ashadu anna Muhammadan Rasool Allah

اَشْهَدُ اَنَّ مُحَمّدًا رَسُولُ اللهِ / Ashadu anna Muhammadan Rasool Allah

Not knowing the rest, I watch the boys as they finish gently mumbling the prayer. More lyrics from that Cranberries song seep into my brain:

“But you see, it’s not me, it’s not my family,

in your head, in your head, they’re fighting…

With their tanks and their bombs

and their bombs and their guns

In your head, in your head,

they are dyin'...”

But it is me. It is my family. And it’s our tax dollars too. All of us shoulder the mess of history. Maybe some more than others. A few people on my maternal side were Zionist machers in Detroit, Michigan. An uncle of mine is an IDF veteran. One of my mom’s great-uncles, Simon Shetzer, was executive director of the Zionist Organization of America in the early 1940s, at the height of the Nazi holocaust. A memorial forest was planted for him in Israel by the Jewish National Fund. He ran the organization at a time when restrictive immigration quotas in the U.S. and Britain led many European Jews to Palestine. Those who came found their Zion – but at what cost? More recently, the ZOA, among other prominent national organizations like the Anti-Defamation League, has outright defended or slow-walked condemnation of white fascists in the U.S. accused of antisemitism while hounding Black and Arab people facing similar allegations.

On the other side of my family, my paternal great-grandfather, Tsvi Hersz Szerman, was a member of the Jewish Labor Bund in Russian-occupied Poland. A passionate admirer of Karl Marx and Leon Trotsky, Hersz was described by my late grandfather (his son) as “a ridiculous idealist, hero for the people, defender of the masses… "He marched to the beat of a different drum and was born too soon.” Hersz did a short stint in prison after involving himself in the failed 1905 revolution against the oppressive rule of Tsar Nicholas II. Family legend has it that he managed to escape execution by hiding beneath the robes of a Russian Orthodox priest. More likely was that an officer was bribed to secure his release or that another relative took his place.

Learning about Hersz and my family’s Bundist past led to an inevitable encounter with doikayt, the Bund’s Yiddish philosophy of “here-ness.” Contrasted against Zionism’s “there-ness,” doikayt pushed the boundaries of imagining Jewish self-determination, championing a world where we could exist diasporically alongside a plurality of other peoples. Doikayt was embodied through the Bundists’ attempts at building national-cultural autonomy in the Russian-occupied territories — which had already existed in some form prior to the Partitions of Poland in the late 1700s. The Jewish Labor Bund’s political platform would emphasize socialism through an embrace of Yiddish culture while also fiercely rejecting Zionism.

The Bundists, alongside many other Eastern European Marxists, saw Zionism in all its manifestations as surrendering to antisemitism in Europe. For them, the Zionist movement was largely supported by assimilated, bourgeois Jews antagonistic to the Yiddish and Arab working-classes. A number of European Jewish Zionists, including Theodor Herzl, Ze’ev Jabotinsky, and David Ben-Gurion, all displayed the traits of a deeply internalized Jew-hatred. Herzl derided Jewish anti-Zionists in his day as mauschel: a multi-layered German insult and a synonym for “k*ke” that synthesized the weakness of maus (mouse), moishe as a money-grubbing caricature of Moses, and a general disdain for Yiddish as inferior language, or zhargon (jargon). Jabotinsky, father of right-wing Revisionist Zionism, sought to separate the “ugly, sickly” urban-dwelling Yids of the past from the “proud” and “masculine” agricultural Hebrews of the future. Ben Gurion, for his part, in a 1954 conversation with journalist Isaac Deutscher, regurgitated the antisemitic trope of non-Zionist diaspora Jews as “rootless cosmopolitans.” He would also express deep disgust for the “backwards” culture of Arab Jews.

The Zionist movement sought backing from antisemitic and evangelical European Christian elites – men like Lord Arthur Balfour, Kaiser Wilhelm II, and the infamous colonialist Cecil Rhodes. Herzl himself saw these kinds of relationships as beneficial to Zionism, writing in his journals, “The antisemites will become our most dependable friends, the antisemitic countries our allies.” These elites hoped Zionist ambitions in Palestine could stem the tide of Yiddish immigrants coming to Western Europe, answering the “Jewish Question” once and for all. Others wished it could prevent Marxist sentiment, spread by revolutionary Jewish activists, from infecting the rest of the continent. The latter perspective belonged to future British prime minister Winston Churchill, who anxiously protested the growing influence of the “International Jews” in a 1920 article written for the Illustrated Sunday Herald, “Zionism versus Bolshevism:”

“From the days of Spartacus-Weishaupt to those of Karl Marx, and down to Trotsky (Russia), Bela Kun (Hungary), Rosa Luxembourg (Germany), and Emma Goldman (United States), this world-wide conspiracy for the overthrow of civilisation and for the reconstitution of society on the basis of arrested development, of envious malevolence, and impossible equality, has been steadily growing. [...] It has been the mainspring of every subversive movement during the Nineteenth Century; [...] The cruel penetration of [Trotsky’s] mind leaves him in no doubt that his schemes of a world-wide communistic State under Jewish domination are directly thwarted and hindered by this new ideal, which directs the energies and the hopes of Jews in every land towards a simpler, a truer, and a far more attainable goal. The struggle which is now beginning between the Zionist and Bolshevik Jews is little less than a struggle for the soul of the Jewish people.”

While the Jewish Labor Bund was ahead of the wider Russian communist movement in mobilizing revolutionary drive among the Yiddish masses, they soon faced pushback from the emergent Bolshevik and Menshevik factions of the Russian Social Democratic Workers Party (RSDWP; predecessor to the Soviet Communist Party). The Bund was derided by Vladimir Lenin for its nationalistic considerations (though he’d take a more favorable stance on national liberation later in life). For Lenin, proletarian unity was the chief objective of socialist organizing. Bundists responded with disdain at the early RSDWP’s approach to the “National Question.” Caught between the assimilationist and chauvinistic “proletarianization” of Russian Marxists, the escapist nationalism of the Zionists, and the ultra-traditional conservatism of the Haredim, the Bund grew increasingly isolated.

A period of brief respite for Jews under the Soviet Union after the 1918 Russian Revolution came to an abrupt end. Mass exodus spurred by the Nazi’s genocidal colonization of Eastern Europe was accompanied by counter-revolutionary discrimination brought by Soviet premier Josef Stalin in the USSR. The dual horrors of settler-colonialism and social imperialism, competing processes of Westernization, Sovietization, and Zionization among different Jewish populations, as well as shifting dynamics of class and race over subsequent decades, left the radical traditions of the Bund in tatters. Its contributions are largely forgotten or dismissed today. Practically all mainstream Jewish political and religious formations in the West and the Soviet states gradually took on pro-Zionist positions, especially after Israel’s “miraculous” victory in the 1967 Six-Day War. Zion was an addictive drug to the broken Jewish heart, and a highly militarized State of Israel became a fortified boon to the dominant American neoconservative agenda, particularly in the aftermath of the 1991 Gulf War.

Some managed to see beyond the fantasy. In a piece published for The Nation, “Open Letter to the Born Again,” the famed writer James Baldwin interrogated the social nature of the Jewish collective relationship to Israel and the positionality of Jews in the European imaginary:

“…absolutely no one cared about the Jews, and it is worth observing that non-Jewish Zionists are very frequently anti-Semitic. The white Americans responsible for sending black slaves to Liberia (where they are still slaving for the Firestone Rubber Plantation) did not do this to set them free. They despised them, and they wanted to get rid of them. Lincoln’s intention was not to “free” the slaves but to “destabilize” the Confederate Government by giving their slaves reason to ‘defect.’ […] “It has always astounded me that no one appears to be able to make the connection between [...] the Catholic Church—in the history of Europe, and the fate of the Jews [...] Does no one see the connection between The Merchant of Venice and The Pawnbroker? In both of these works, as though no time had passed, the Jew is portrayed as doing the Christian’s usurious dirty work.” [...] “…the state of Israel was not created for the salvation of the Jews; it was created for the salvation of the Western interests. This is what is becoming clear (I must say that it was always clear to me). The Palestinians have been paying for the British colonial policy of “divide and rule” and for Europe’s guilty Christian conscience for more than thirty years.”

I was never taught the history of the Jewish Labor Bund. I only learned about it from the writings of my late grandfather, a WWII veteran, which my dad and I started seriously reading in my early twenties. I came to political consciousness in the reactionary Islamophobic milieu of the United States after 9/11 and Second Intifada. Mainstream Jewish institutions filtered a version of Palestinian identity that was generally presented as a composite of all those deemed to be the worst villains in Jewish history (or incidentally the Christian West): from Amalek to the Philistines, from the Romans to the Nazis and the Soviets, from the Muslim Brotherhood to Iran. Growing up in a liberal Zionist, Reconstructionist shul, memories of Oslo were trapped within the rhetorical husk of a two-state solution; talk of it hovered between quiet bites of bagel as adults sneakily stuffed their mouths before the lunchtime brachot. For the most part, people in my immediate community were disgusted with the Occupation and bemoaned the rise of Kahanists in Israel’s government.

This fascistic element was typically spoken about as if it were an aberration from the Zionist norm; it was either blamed on Arab Jewry or treated as separate and unrelated from the earlier acts of cruelty perpetrated by predominantly Ashkenazi paramilitary fighters in the Haganah, Irgun, and Lehi (who would merge into the official units of the IDF, Shabak, and Mossad). Nostalgia for Israel’s Labor Zionist government reflected a failure of understanding among Jewish communities over how Zionist ideology had a totalizing role in enabling the destruction of Palestinian life. Constant fear-mongering by liberal Zionists over Hamas and Iran effectively justified the status quo in service of Jewish safety, neutralizing attempts at meaningful action. Efforts to “foster dialogue” were riddled with asymmetrical equivocations and the coddling of Jewish feelings. The shallow humanism of contemporary liberal Zionists addressing today’s “Palestine Question” tragically mimics the tone of U.S. president Thomas Jefferson in his 1820 letter to John Holmes on the Missouri Compromise, regarding the expansion of slavery into newly colonized territories:

“I can say with conscious truth that there is not a man on earth who would sacrifice more than I would, to relieve us from this heavy reproach, in any practicable way. The cession of that kind of property, for so it is misnamed, is a bagatelle which would not cost me in a second thought, if, in that way, a general emancipation and expatriation could be effected: and, gradually, and with due sacrifices, I think it might be. But, as it is, we have the wolf by the ear, and we can neither hold him, nor safely let him go – justice is in one scale, and self-preservation in the other.”

“Justice is in one scale, and self-preservation in the other.” This type of naked moral compromise is innate to the thinking of liberal Zionism. One could say it is an indictment of Western liberalism writ large. In the present, we can simply switch out the ‘wolf’ of chattel slavery for the Occupation of Palestine. In his own time, Jefferson’s thinking was overrun with fear driven by the Haitian Revolution and the threat of Caribbean slave revolts inspiring African peoples in the Southern United States to rebel against the American government. Similarly, the fear of rebellion by Palestinians constantly haunts the Zionist imagination. Thus, the egalitarian mind reaches only so far: the “Other’s” liberation is permissible, but only gradually, and so long as they behave — so long as the oppressed do not take revenge, however justified that vengeance may be.

A decade ago, when I returned to the U.S. from my group trip to occupied Palestine following the 2014 massacres in Gaza during “Operation Protective Edge,” I clearly remember watching reports come out of Ferguson, Missouri; cops with rifles and armored trucks beat protestors speaking truth to power against the murder of Michael Brown. What erupted was an American Intifada — and this description is more than just mere wordplay. The St. Louis County Police Department was one of a number of U.S. law enforcement outfits with officers who had participated in “Deadly Exchange” counterterrorism training with Israeli security divisions, sponsored by groups like the ADL and AIPAC. Nothing was the same for me after coming back from my trip that summer. The experiences I had then were responsible for driving my general disillusionment with Zionism, as well as the United States.

What unity might we find if we elucidate

a different historical frontier of oppression,

perhaps 1492, when anti-Jewishness,

Islamophobia, anti-Blackness,

and anti-indigenous sentiment

all ascended together across the world?

But the history I’d soon find buried in the Bundist past led me to draw parallels to the current political situation. The dynamics of resistance in Gaza today resemble alliances forged between Jewish groups in the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising; communists, Zionists (both Labor and Revisionist wings), anarchists and Bundists all united together to survive. They established underground networks with other ghettos in Bialystok and Minsk. Jewish partisans received essential aid from escaped Soviet POWs, as well as members of the Polish and Lithuanian resistance. Of course, the Jews resisting Nazi colonization were joined by thousands of additional Jewish and non-Jewish soldiers serving in the armies of the Soviet Union, United States, and Great Britain.

The Palestinian factions in Gaza have maintained sumud, organizing across ideology in the face of annihilation. The present-day Joint Operations Room of the Palestinian Resistance functions under a wartime methodology, the “Unity of Fields,” tying together all battlefronts engaged by the larger Axis of Resistance – the alliance of militants and armies including various regional actors such as Hezbollah in southern Lebanon, Ansar Allah in Yemen, the government of Syria, Iraq’s Popular Mobilization Forces, and the Quds Force of Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard. The fight to stop a genocide in Palestine has resurrected a shared, region-wide (al-Shami) identity, groundbreaking Sunni-Shi’a cooperation, and a united opposition to the hegemonic aims of Western monopoly capital that, for the last twenty to thirty years, has masqueraded as a “Global War on Terror” bestowing the “gifts” of liberal democracy (read: destabilizing countries to capture new markets).

Iran’s involvement is typically brought up in order to discredit the entire project of Palestinian sovereignty. This is hardly new. The same detractors would invoke the Soviet Union or pan-Arabists in earlier times when delegitimizing the Palestinian struggle. Surely I do not assume any political leader anywhere to be wholly benevolent. It is necessary for people to retain discernment against different forms of dogma and maintain a healthy skepticism. Those who castigate the “lesser evilism” of US domestic politics should caution themselves from projecting the same notion onto the world stage. Still, regarding Palestine, we can borrow from the reflections of Leon Trotsky. In 1938, Trotsky suggested that even if an anti-colonial movement rebelling against a “democratic imperialism” is supported by a “fascist imperialism” for the latter’s own political purposes, those anti-colonial movements still deserve aid from the revolutionary groups active in both imperialist states. Different fights for liberation can mutually reinforce each other. It is therefore absolutely possible to support the resistance in Palestine against Zionism and critique the internal contradictions of clerical-bourgeois elements in states like Iran and also apply severe scrutiny to U.S. interventionism. When we wage our struggles over one another, principles become fragile and we all lose.

As it stands, the Soviets are no more. The Sunni states have normalized. The PA is a police state. The West plays a bait and switch on the “Palestine Question.” The United Nations is utterly impotent. Who are Palestinians to turn to? Is it the United States, as the Biden-Harris administration continues to ship to Israel the very arms used to slaughter their own? Do pearl-clutchers in the Global North really expect people in Gaza or the West Bank to coup their own quasi-governments on the backs of Israeli tanks? What is “peace” without justice, “peace” in a genocide – without any affirmative political initiative, without any assurances of sovereignty, reparation, or return? How racistly out of touch can people possibly be? Here’s what I must ask the detractors: given the extraordinary military and economic support provided by the United States and other Western governments, supplemented by companies in the private sector, how is Israel truly sovereign and not a proxy itself? It may as well be the 51st state, with the billions it receives from the American government (as Appalachia, riddled with crumbling infrastructure, is thoroughly flooded by Hurricane Helene)! And, in comparing Palestinian militancy to Jewish resistance during the Shoah, what might have happened during WWII if the majority of citizens in Allied countries firmly refused to fight the Axis powers because many Jews held socialist sympathies and fought in Stalin’s Red Army?

Our present juncture leaves us with so many questions: why are Jews left bearing the responsibility of rehabilitating “Europe’s guilty Christian conscience,” as Baldwin put it? What can self-determination look like beyond the mitzrayim (“narrow place”) of the nation-state paradigm? What if we removed the Nazi holocaust from being the singular reference point for global suffering and ultimate evil? How might the Shoah and Nakba exist together in discourse instead of the former’s victims being used to silence the victims of the latter? What unity might we find if we elucidate a different historical frontier of oppression, perhaps 1492, when anti-Jewishness, Islamophobia, anti-Blackness, and anti-indigenous sentiment all ascended together across the world? In her 2016 polemic “Whites, Jews, and Us: Toward a Politics of Revolutionary Love,” French-Algerian activist Houria Bouteldja excoriates the liberal affinities of the Jewish political establishment in France while prophesying the coming conflict among Jews over Zionism:

“…you have abandoned the ‘universalist’ struggle by accepting the Republic’s racial pact: white people on top, as the legitimate body of the nation, us as the pariahs at the bottom, and you, as buffer. But in an uncertain, uncomfortable in-between. [...] It’s the privilege of the dominant class to know our weaknesses. To be part of the master’s race. That’s what we all want. So, then they gave you Israel. [...] “Whether you like it or not, anti-Zionism will be, along with an indictment of the nation-state, the primary site of this endgame. It will be the site of the historical confrontation between us, the opportunity for you to identify your real enemy. Because fundamentally, it’s not with us that you must be reconciled but with white people. […] Anti-Zionism is that territory in which two primary victims of the Israeli project come to light: Palestinians and Jews. It is also where its primary beneficiary appears: the West. […] When you break with Zionism, you take the shortest route to put an end to the infernal cycle in which Zionism and anti-Semitism feed off each other endlessly, and in which you will always lose yourself.”

The essence of Bouteldja and Baldwin’s analyses reveal the following: Herzl’s dream inspired Hitler’s last laugh. To be part of the master’s race…still doing the Christian’s dirty work. With the Jewish image twice laundered by Europe, once through the appropriation of Christ’s suffering (in medieval times) and twice through curating a messianic hunger for Zion (in the modern day), Jewish victimhood is deified by the Western world; Jews, once the victims of internal colonization within Europe, are ontologically transformed — with willing collaborators — into shields of Western supremacy, seduced by liberal philosemitism and converted into morality detergent for the “Judeo-Christian” pact. Deborah Feldman, author of the memoir-turned-Netflix series “Unorthodox,” articulates the contours of this philosemitism in an interview in which she discusses her new book “Judenfetishce,” written about her experience of antisemitism in a post-Zionist Germany: “Philosemitism is antisemitism. It’s the other side of the coin, but it doesn’t allow the object of its love or its hatred to be a human being, to be an individual. It dissolves the object of that affection or hatred into a projection, and if we as Jews don’t submit to this projection, we are then the enemy that must be eliminated; we are disturbing this romantic, fetishizing relationship between Germany and its ‘beloved’ Jews – its beloved projection of Jews.”

Feldman rightfully points out that the benefits of this social contract are ultimately conditional. Those like herself who challenge or betray the ‘Jewish projection’ are disparaged by Euro-American fascists and negated as self-hating, ignorant “Un-Jews” by the American Jewish and Zionist establishments. Betrayers may be punished or persecuted for their support of Palestinians. Physical harm towards these dissident Jews is encouraged by Zionists. This modality of violence can be considered part of what Israeli historian Raz Segal describes as ‘state-settler antisemitism’, a phenomenon targeting different categories of Jews who’ve been marginalized by the Jewish and Zionist mainstreams: anti-Zionists, non-Zionists, Arab Jews, leftists, African Jews, etc. All this being said, it is essential for us to acknowledge that Palestinians and the peoples of the Global South have been made to pay the primary, apocalyptic price for the West’s judenfetische. The philosemitic reality is all the more true in light of dangerous language recently used by both Donald Trump and Joe Biden as they have jockeyed for Zionist votes and donor support, Jewish and Christian alike, at the expense of Palestinians, Arabs, and Muslims in the 2024 U.S. presidential election.

Humanity needs a revolution of ideals. Palestinians need their freedom. Jews must do away with the golden calf of goyishe ethnonationalism while de-assimilating from settler liberalism. We must resist the ‘blood and soil’ implication of synagogues pushing a fundamentalist view of ahavas yisroel onto future generations. We can use this opportunity to sharpen a unique counter-theology in order to strengthen a radically inclusive chavurah (”fellowship”). Ahavas yisroel, truly loving the “Land of Israel,” means decolonizing Palestine. Loving the “People of Israel” means supporting anyone who chooses to wrestle with the angels of God — those who question authority, contend with the cosmic, challenge the “natural order,” and work to diligently disassemble systemic oppression. The Kaplanian, non-supernaturalist model of divinity in Reconstructionist Judaism defines “God” as the sum total of all creative forces that equal a human being’s fulfillment and centers our collective ethical refinement. Rabbi Mordecai Kaplan knew the sting of excommunication from his Jewish community for his ideas, akin to today’s dissenters. Make no mistake, Kaplan, at his core, saw himself as a cultural Zionist. Still, his concept of Judaism as an ever-evolving process of spiritual expression – one that emphasizes behavior over belief and is constantly renewed l’dor v’dor (generation to generation) – may be something worth composting.

Zionism is a ghetto of our own making; it is anti-Palestinian and it is anti-Jewish. Taking our cues from the Palestinian Resistance, we can throw away this fetid contract with the West and break out of the ghetto.

As Jews, aligning ourselves with the diasporist ethos of doikayt can help deprogram the cultural exceptionalism blinding so many of us. We will shatter the sterile binary of particularism versus universalism, liberating a plural and multipolar Jewish existence beyond the confines of Zionist hegemony. Under a new framework, revitalized expressions of Jewishness can support the cause of Palestinian Liberation and redefine the meaning of solidarity. Zionism is a ghetto of our own making; it is anti-Palestinian and it is anti-Jewish. Taking our cues from the Palestinian Resistance, we can throw away this fetid contract with the West and break out of the ghetto. Why chain our imaginations to the so-called “pragmatic” or supposedly conventional? Doikayt can, and must, reinforce sumud in the context of shared struggle. Like the rock musician Seal once sang, “But we’re never gonna survive, unless we get a little crazy.”

The adhan ends and I decide to play the boys some other tunes. The song “Beautiful Life” by the late musician Chuck Brown (Washington, D.C.’s legendary “Godfather of Go-Go”), featuring the rapper Wale, comes up in the queue. Being from DC and developing into a devoted representative of my hometown, I never miss an opportunity to put anyone on to some go-go if I can help it. Bashar bobs his head to the funky percussion native to the classic go-go sound. He and Khaled try to hum some of the melody:

“What a Beautiful Life!

All that I got,

All that I need,

I got you, and baby,

You got me

What more could I ask for?

Beautiful Life!”

Prayers, music, and cartoons all work to soothe an aching spirit. This fleeting moment is an oasis of joy for us. Soon enough, I will return to Khirbet Susiya. During a late afternoon, I stare into the eyes of a teenage settler riding a donkey as he threatens a Palestinian boy with his stick: the settler is too young to be this vicious. His viciousness reminds me of Hitler Youth types who once humiliated my grandfather as a boy on the streets of Newark, New Jersey in the 1930s. This young settler in the West Bank is a child soldier for Jewish supremacy, for manifest destiny, for Zion. Palestinians are subhuman to him. Nasser tells me to call the police. I dial the emergency number. They answer, and I ask for someone who speaks English. I say we are being harassed by settlers. “Is this Palestinian?” The officer asks. I tell her I’m a Jewish American citizen. She asks again, “Is this Palestinian?” She’s over it; I can hear it in the tone of her voice. To argue is useless. “Sure,” I reply. The officer takes my number down. The call ends. All too predictably, the cops don’t show up.

Walking around the town one night, I hear the loud music of settlers holding a big concert at the site of the old synagogue. I am reminded of the Nova music festival in Re’im, hosted just outside the ghetto of Gaza. So many people back home just expect Palestinians to endlessly tolerate this. How could you not hate the people who do this, Jew or otherwise? How helpless does one have to be to appear sympathetic? What good is there in being a noble, polite, and respectable victim? It’s never long before someone snaps. But if a Palestinian responds with violence, they will be called a “terrorist” or a “savage.” If a Jew acts out, it is warped into “self-defense.” The following passage comes from my grandfather’s journals:

“The paradox of humane behavior in society (society, a paradox in itself) lays bleach boned in the face of war. Society which, through some mental quirk, deems itself civilized, is a blatant contradiction…”

Grandpa wrote about how, as a soldier in Europe, he’d vengefully burn the Magen David into Nazi homes, shredding portraits of Hitler as he went. Nowadays, Israeli police brand the Star of David into Palestinian flesh while IDF soldiers sodomize Palestinians in torture camps and record themselves toying with women’s lingerie stolen from homes in Gaza. Israeli president Isaac Herzog tells us this is a war “to save Western Civilization” — the very same “civilization” that murdered us in the Crusades, that expelled us from Iberia, allowed us to die in camps, and refused to allow our safe return home post-slaughter. No thank you. To hell with Herzog. To hell with all of it. The hypocrisies of Western civilization haunt me. The contradictions haunt each of us, perhaps now more than ever. It is precisely because of this that we must work to abolish them.

Holding the line is not enough. We can’t stay on the defensive. We need to escalate. Constant mobilization has led to burnout at the expense of sustained organizing. Understanding the physics of revolt requires sharper science and a diversity of tactics. Some individuals, like economics lecturer Marcie Smith and journalist Vincent Bevins, have offered worthy critiques on the horizontalism prevalent in the “mass protest decade” of the 2010s, extrapolated, at least in part, from the neoliberal nonviolent strategies of lauded “Cold War defense intellectual” Gene Sharp. Sharp was a leader at the Center for International Affairs (CIA) at Harvard University, a devil’s den for morally repugnant “Cold Warriors” and corporate kingmakers. I mention this because it is worth noting that Gene Sharp also happened to be a mentor to Nonviolence International’s Mubarak Awad. If his techniques cannot be reverse engineered from the NGO frame, then they may be turned against us by the very powers we aim to oppose. We must learn from the pitfalls of the Occupy, Black Lives Matter, LandBack, and Palestine solidarity movements, as well as everything in-between. It is true, unfortunately, that we do not have the privilege of slowing down. Empires never sleep. So we shall learn as we go. Vigilance is essential. When it comes to fighting against Zionism, we can all do better in this regard.

At the playground in Susiya, I play Uno with the kids as their mothers, grandmothers, older sisters, and aunts chat amongst themselves. Close by, the men will bow for salat. A distant rumbling roars in my ears, drowning out the adhan ringing from Yatta. The noise is caused by Israeli F-16’s soaring off from their base in the Naqab to do God knows what. Faint lights glow in the dark, on the western horizon. Light from Gaza.

Zombie, Zombie, Zombie-ie-ie….

Time to pray.

A week after my return to the U.S., I paid a visit to Mount Carmel Cemetery near my Ridgewood apartment in New York City. This graveyard is only one piece of the massive Cemetery Belt stretching across Queens. Walking into Mount Carmel, various languages can be seen on the headstones: Hebrew and Yiddish, English and Russian, possibly Bukhori (the Tajiki Persian dialect of Bukharan Jews).

Many Jewish people recognized for their cultural achievements or honored in some way are buried here. There’s Leo Frank, victim of the infamous Georgia lynching, which serves as the premise of the critically-acclaimed musical “Parade;” Sholem Aleichem, the renowned Yiddish playwright whose stories about Tevye the Dairyman evolved into “Fiddler on the Roof;” Abraham Cahan, founder of the Jewish Daily Forward newspaper; Vladmir Medem, an early ideologue of the Jewish Labor Bund. Harry Houdini, the legendary magician, is even buried nearby. In any case, there’s no shortage of dead Jews here.

I chose to visit the grave of Szmul Zygielboim, ז״ל, Bundist leader of the Polish government-in-exile during WWII. Zygielboim famously attempted to warn the Allies of Nazi crimes; their failure to stop the worst of the Shoah, coupled with the belief that his family had perished in the liquidation of the Warsaw Ghetto, drove Zygielboim to commit suicide in protest over the world’s inaction. His cremated remains were brought over to New York from London and buried here by comrades in Der Arbeter Ring, known today as The Workers Circle. Some of his final words are imprinted on the gravestone:

I cannot remain silent

I cannot go on living

When the remnants of the Jewish People

Whom I represent

Are being annihilated.

My life belongs to

The Jewish People

In Poland

And therefore

I give it to them.

Taking a rock from my pocket, I place it beneath a stone sculpture atop the grave representing the Eternal Flame. It is from Susiya. The Hebrew word for pebble is tz’ror – “bond.” The stone sits on the gravestone as a spiritual interlocutor, binding the soul of the dead to the cradle of remembrance. The Mourner’s Kaddish flows from my lips: Yisgadal veyiskadash shemey rabo…

I close my eyes and am transported back to the South Hebron Hills. I’m on a break from shepherding. The father from my primary host family sits with me under the lookout tree. We stare out at Jewish Susya. He is a kind man, an adoring parent, with the heartiest laughter. I enjoy watching him goof around with his younger children. He has taught me much about this place.

“The view is beautiful,” I say to him.

“It would be more beautiful if there weren’t any settlers. How can they raise their children like this?”

“I wish I could say. It seems that their parents are too busy praying. They don’t stand for much other than themselves.”

“What do you stand for?”

It takes me a second to collect my words and put them in Google Translate. An era passes in the flash of a moment. Admittedly, I am caught off guard.

“I stand for truth and justice…and doing right by others.”

I want it to be true… these virtues feel like chalk in my mouth. I fumble my convictions. Where is the line between being for others and being for ourselves? Am I here for him or for me? I decided two weeks ago that I simply want to show up – it’s a start. And that may have to be satisfactory for now. If more people did this work, more U.S. Jews, maybe it could help shift the balance. To be clear, this will not stop genocide. Resistance will do that. Or some massive geopolitical force. Although, if the folks in Khirbet Susiya feel any safer because of this, then it’s worth it, right? I think it’s what any able-bodied person should do if they can.

“It feels like the whole world, everything from the past 70 years, is turning a corner. Not just in Palestine. America, Russia and Ukraine, China, Sudan…things are definitely changing…”

“Yes…hopefully for the better?”

“Yes, for the better, inshallah.”

“Inshallah…”

“When will you come back?” asks a couple of the Susiya kids before I leave Masafer Yatta. I tell them something earnest but truthfully I have no idea. I do trade some contact information with my new friends. I let my “host dad” know that it was an honor to learn and live with him, even if for a short time. He tells me I was part of his family, and, god willing, we will stay in touch. An Israeli activist was kind enough to offer me a ride to the airport. It was Saturday, and I completely forgot to account for the fact that there is no public transit out of Jerusalem on Shabbat. We are Jews so, unlike our Palestinian comrades, I do not have to anticipate getting held up at a checkpoint. I will arrive in Tel Aviv a little earlier than anticipated.

With a couple hours to kill before my flight home, I stroll the streets. I hope to dip my feet in the Mediterranean for a moment. Many of the families I met in Masafer Yatta would not be able to come here easily, if at all. There are people in Susiya who have not even seen the sea. I can – so can all of the Israelis here on this beach while they laugh, lounge, swim, and play kadima. An hour south of here soldiers continue turning Gaza into a killing field. A couple hours to the west and the laws of force maintain colonial apartheid. Compared to the more conservative Jerusalem, the sight of the beach in Tel Aviv represents the liberal dimension of Israel’s “Zone of Interest.”

Left: The walkway to the beach in Tel Aviv / Occupied Yafa. RIght: A corridor in the Old City of Jerusalem / Al-Quds, with the Qubbat as-Sakra (Dome of the Rock) in the distance.

At Zygielboim’s grave, I meditate on the United Nations officials, the murdered Palestinian journalists, and other aid workers who have tried to warn us about the atrocities in Gaza and how their calls to the West have largely gone unanswered. I think about Mohammed Abu Khdeir, an East Jerusalem teen kidnapped and murdered ten years to the day I left for the West Bank. I think of Shireen Abu Aqleh, Refaat Alareer, Hind Rajab, Aaron Bushnell, Rachel Corrie. I think about the 1,200 killed on October 7, both by Hamas fighters and via Israel’s notorious Hannibal Directive. I think about the 42,000 – possibly upward of 200,000 according to The Lancet – slaughtered in Gaza on top of the 719 killed in the West Bank. Countless bodies buried beneath rubble; thousands of political prisoners held in administrative detention without charge.

“There are decades when nothing happens; and there are weeks when decades happen,” or so said Vladimir Lenin. Since I returned to the U.S., Multiple genocides continue around the world: in Palestine, Congo, Sudan, and Tigray. Donald Trump has been nearly assassinated, twice. Joe Biden suddenly dropped out of the presidential race, passing the baton off to vice president Kamala Harris, who has rejected any suggestion of enacting an arms embargo on Israel and has bragged about receiving the endorsement of Bush-era neocons. The symbolism around her candidacy and the false catharsis it inspires among a swath of the U.S. electorate (a disappointing but natural evolution of Hilary Clinton and Barack Obama’s previous presidential bids) are being used by the Democratic Party to capture radical energy away from protesting the genocide they’ve enabled. The Knesset overwhelmingly rejected Palestinian statehood, pissing on the carcass of Oslo. The International Court of Justice finally recognized the illegality of the Zionist Occupation, only for Israel to launch its biggest invasion of the West Bank in years, dubbed “Operation Summer Camps.”. Benyamin Netanyahu, a wanted war criminal, delivered his address to the U.S. Congress and received massive applause from both sides of the aisle. Ismail Haniyeh, leader of Hamas’ political bureau, was assassinated in Tehran. Yahya Sinwar took his place. Israel massacres hundreds in Beirut and southern Lebanon including Hezbollah’s longtime secretary-general, Hassan Nasrallah. Netanyahu, desperate to stay out of prison and to hold power, is willing to wage war to appease his fragile base. Officials in the Israeli government with considerable support (including from U.S. hawks and Western evangelical allies) thirst for “security” via conquest and a messianic kingdom that might redeem the failures of the War on Terror — not just between the Jordan River to the Mediterranean Sea, but with a “Greater Israel” that stretches from the Euphrates River to the Nile.

I watch a video on Instagram of a family I knew in Khirbet Susiya getting attacked by a mob of settlers. I slept in their home. I message members of the family over WhatsApp. No one was seriously injured. They send me pictures of damaged property. In a second clip, one of the Israeli activists I met is brutalized by a settler-soldier. A third video depicts Hamdan being threatened with rape by a settler named Shem Tov Lusky. "You look sweet. You are my bitch. You look so fresh," Lusky tells Hamdan in Hebrew. "I will be happy to sit with you in jail someday. I would be happy. You know Sde Teiman..? Rape for the sake of God, as they say. You understand what I mean?” Another activist, Ayşenur Ezgi Eygi, is killed by Israelis while doing solidarity work with Faz3a and ISM near Nablus. We were the same age. A month and a half separated my trip from hers.

I am so far away and there is so much disaster. The feeling of helplessness is overwhelming. Most times I don’t know what to do with myself. I see pieces of children, the limp bodies of infants, their bereft parents wailing on my social media feed almost every day. I want to cry — the tears don’t come. But rage? I know rage well. It hangs there just beneath the surface, always. My rage could swallow the Earth. The more I come to know, the more sorrow I feel for the world. But the more I see, the less I know for sure. So, there is that. Baldwin once said, “I am not a pessimist because I am alive.” Pessimism can too easily devolve into self-fulfilling prophecy. It’s a cop out, especially for those of us in the “belly of the beast.” When I feel myself ebb and flow between hope and despair, I look to resistance. I recommit to action; to the great work of tikkun (transformation/repair), and to doikayt. I seek to house my neighbors. I seek to get folks fed. I make good trouble. I study, train, disrupt, and raise hell. Gaza lives. The West Bank is rising. Palestine is alive. Resistance movements push forward because the cause of life demands it. History demands it. The martyrs, shahada and kedoshim, all demand it. My friends in Susiya demand it. So I will be sumud.

When הַשֵּׁם (Hashem), the One in Many and the Many in One, cries out to us:

"Ayeka (where are you)?"

We respond:

"Hineni (I am here)!"

So I am here...

Here to hold the line...

Until every wall falls.

"The most important war

Is the war against the wall built around our eyes and minds.

If we free ourselves from all these thoughts,

That 'I am lesser than them and merely a chess piece that everyone plays with…

'I am, I am, I am…'

We keep lessening ourselves.

No, my dear.

We are capable of change, of rising up and resisting.

But start with yourself.

~ Bassel Al-Araj, the “Engaged Martyr,”

Killed by Occupation forces on 6 March, 2017

Follow Sam Sherman on Instagram at @samszerman.